DATA SOURCE(S): 12,24

Common Name(s): Coromandel ebony, tendu, kendu, East Indian ebony

Scientific Name: Diospyros melanoxylon

Distribution: Primarily India and Sri Lanka (the wood’s name comes from the Coromandel Coast in southeastern India)

Tree Size: 40-65 ft (12-20 m) tall,

1-2 ft (.3-.6 m) trunk diameter

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): .99, 1.24

Average Dried Weight: 77.7 lbs/ft3 (1,245 kg/m3)

Janka Hardness: 3,960 lbf (17,600 N)*

*Estimated hardness based on specific gravity.

Modulus of Rupture: 36,250 lbf/in2 (250.0 MPa)†

Elastic Modulus: 2,610,000 lbf/in2 (18.00 GPa)†

Crushing Strength: 10,150 lbf/in2 (70.0 MPa)†

Shrinkage: Radial: 5.4%, Tangential: 8.8%,

Volumetric: 14.4%, T/R Ratio: 1.6 † Very High

†These strength/shrinkage values were taken from only one source,[1]Gérard, J., Guibal, D., Paradis, S., & Cerre, J. C. (2017). Tropical timber atlas: technological characteristics and uses. éditions Quæ. p 129. which refers more broadly to “Asian black ebony” as a species grouping. The MOR value in particular seems abnormally high for ebony.

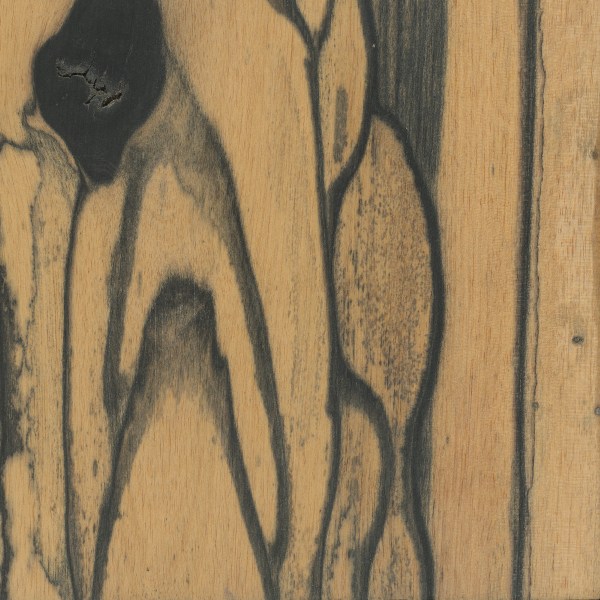

Color/Appearance: Heartwood is a jet black, sometimes with reddish brown or purplish streaks. Sapwood is pale yellow to pink, and is clearly demarcated from the heartwood. Ironically, the very best quality ebony looks like black plastic.

Grain/Texture: Grain is typically straight or sometimes irregular, with a fine, uniform texture. Has a high level of natural luster.

Rot Resistance: Portions of black heartwood are very durable regarding decay resistance.

Workability: Overall difficult to work on account of its density and strong blunting effect on cutting edges. Can be difficult to dry, with checks or other drying defects developing. Can be difficult to glue, with one study[2]Narayanamurti, D. (1957). Die Bedeutung der Holzextraktstoffe. Holz als Roh-und Werkstoff, 15(9), 370-380.[3]Chunsi, K. S. (1973). The gluability of certain hardwoods from Burma (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). that mentioned the extractives of Diospyros melanoxylon causing weaker glue joints—even observing a transmission of this weakness to other species when treating them with extractives from this ebony. Ebony turns superbly, and takes a very high natural polish.

Odor: No characteristic odor.

Allergies/Toxicity: Although severe reactions are quite uncommon, ebony in the Diospyros genus has been reported as a sensitizer. Usually most common reactions simply include eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. See the articles Wood Allergies and Toxicity and Wood Dust Safety for more information.

Pricing/Availability: Although Coromandel ebony was one of the original ebonies of commerce (along with Diospyros ebenum), it’s seldom available today. Expect prices to be very high, and availability to be very scarce. Other ebonies such as Gaboon or Macassar are more commonly available, though both are also very expensive.

Sustainability: This wood species is not listed in the CITES Appendices, is currently not evaluated by the IUCN for inclusion on the Red List. This absence of any evaluation is notable, as Coromandel ebony was a historically exploited commercial species, and the IUCN has evaluated several hundred Diospyros species, including many other species that have been harvested and used for ebony. (Perhaps an evaluation is pending, as the closely related D. ebenum is listed as Data Deficient and has not been updated since 1998.)

Common Uses: Inlay, carving, musical instrument parts (piano keys, bridges, nuts, etc.), and turned objects.

Comments: Closely related to Ceylon ebony , both woods are also sometimes referred to as East Indian ebony or simply Indian ebony.

Not to be confused with African blackwood, whose scientific name (Dalbergia melanoxylon) is sometimes confused with Coromandel ebony (Diospyros melanoxylon).[4]Both the 2010 and 2021 editions of the USDA’s Wood Handbook contain a typo in section 3-3 referring to African blackwood as Diospyros melanoxylon. Despite its jet-black heartwood, African blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon) is actually more correctly a rosewood than an ebony, though in practice it really is one of the best “ebony” species.

The Latin melanoxlyon comes from the Greek melano which means black, and xylon which means wood. Species names can be re-used in a lot of different genera. For instance, rubra means red, so you can have red oak (Quercus rubra) or red elm (Ulmus rubra)—both use the same rubra species name but are in unrelated genera.

Images: Drag the slider up/down to toggle between raw and finished wood.

A special thanks to Steve Earis for providing the wood sample (veneer) of this wood species.

Identification: See the article on Hardwood Anatomy for definitions of endgrain features.

Porosity: diffuse porous; growth rings sometimes subtly discernible due to decrease in pore frequency in latewood

Arrangement: solitary and radial multiples

Vessels: medium to large, few to moderately numerous

Parenchyma: diffuse-in-aggregates

Rays: narrow to medium width, normal spacing; rays are just barely visible without magnification

Lookalikes/Substitutes: None.

Notes: None.

Related Content:

References[+]

| ↑1 | Gérard, J., Guibal, D., Paradis, S., & Cerre, J. C. (2017). Tropical timber atlas: technological characteristics and uses. éditions Quæ. p 129. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Narayanamurti, D. (1957). Die Bedeutung der Holzextraktstoffe. Holz als Roh-und Werkstoff, 15(9), 370-380. |

| ↑3 | Chunsi, K. S. (1973). The gluability of certain hardwoods from Burma (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). |

| ↑4 | Both the 2010 and 2021 editions of the USDA’s Wood Handbook contain a typo in section 3-3 referring to African blackwood as Diospyros melanoxylon. |