by Eric Meier

So there seems to be a lot of hub-bub arising recently over the news that rosewoods (as well as Bubinga) are now banned. But is this actually the case? And if so, what does it mean? What is “banned” and what is still allowed?

The short answer is yes.

If you take a look at the updated CITES appendices (as updated and effective January 2, 2017), you will see a new listing that shows “Dalbergia spp.” as well as the three Guibourtia species that are more commonly known as Bubinga, are all listed under Appendix II.

It’s important to note that this “Dalbergia spp.”—though perhaps appearing somewhat innocuous in its Latin botanical naming—denotes the powerhouse genus that contains all true “rosewoods” in the most proper sense of the word (think of such stars as Brazilian Rosewood, East Indian Rosewood, or Honduran Rosewood, just to name a few). This genus also contains a number of other stellar hardwoods that are very similar (and of course closely related) to rosewoods, but lack the actual “rosewood” title in their common name. This includes woods like Cocobolo, Tulipwood, Kingwood, and African Blackwood, just to name a few.

What in the world is going on here?

First off, some clarifications are needed.

What is meant by “banned”? This does not mean that it is somehow illegal to simply own rosewood, or work with rosewood, or even to sell rosewood or the things that you have made out of rosewood. If you are a woodworker, and you have some Bubinga or rosewood, you should be fine (or, at the very least, what went into effect at the beginning of 2017 does not have any bearing on your immediate situation.) Unless you are doing some serious stuff (i.e., Gibson guitar), you probably won’t need to worry about any kind of special investigators coming around knocking on your door asking to see your stash of lumber.

So what does this new development mean?

It all starts with an organization called CITES, which stands for Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. The keyword here is international trade. This new development has impact only for wood that is crossing international borders. If you’ve got wood in your shop, you’re cool—nothing to worry about. But before you write this latest development off as nothing of note, you should consider that most of the exotic wood that woodworkers use comes from other countries—and must by necessity cross international borders. So how is it going to get to you? Where are you going to continue getting that wood? That’s where things get interesting.

A quick primer on CITES

In a nutshell, CITES keeps what might be thought of as a list of endangered species whose trade is regulated or restricted in some way. While there might be other environmental watchdog groups or organizations that would report a tree/wood as being threatened with extinction (such as the IUCN), their reports or observations are more or less just that: observations. They are in no way legally binding. CITES is different. When CITES passes a resolution, it more or less becomes international law (at least in one sense of the word). Thus, it behooves woodworkers and others in the lumber industry to pay special attention to what is going on with CITES, and to have a working knowledge of the ramifications.

The CITES list is divided up into three different tiers, which they called appendices.

-

Brazilian rosewood guitar Photo: Moses Gunesch / CC BY 2.0

Appendix I is the most restrictive category, and includes species that they consider to be threatened with extinction. Probably the best woodworking example of this is Brazilian Rosewood (Dalbergia nigra)—which also includes finished products made of the wood. (Perhaps you may have heard of horror stories of people having their guitars confiscated/forfeited when trying to travel internationally with them.)

- The next tier is appendix II, and basically is described as covering vulnerable species that are at risk and in need of protection to prevent them escalating to appendix I status in the future.

- Appendix III is the least restrictive, and is usually only added for a specific source country to help aid in the enforcement of restricting trade in an international setting.

CITES includes representatives from just about every country in the entire world, and each country/representative is referred to as a “party.” Every three years or so, all the parties meet together in what is known as a “convention of the parties,” or a CoP for short. During this time, the parties will potentially re-evaluate current listings (if a species is recovering and no longer needs legal protection), as well as consider a number of new proposals for species that could potentially be added to the list and receive international protection.

What happened this fall in Johannesburg

From Sept. 24 to Oct. 5, 2016, the convention of the parties number seventeen (CoP 17) was held in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the decisions of this meeting have created quite a stir among the woodworking community. Among other things, there were three main wood types that received protection (restriction) under CITES appendix II. They are, listed in increasing order of prominence, as follows:

Kosso (Pterocarpus erinaceus) This hardwood isn’t commonly seen in North America, but is a Pterocarpus species related to the more commonly seen African Padauk. Appearance-wise, it bears a very close resemblance to the related hardwood Muninga. It’s sometimes referred to as African rosewood, though it’s technically not what would be considered a true rosewood (which, strictly speaking, is comprised only of species in the Dalbergia genus).

Bubinga (Guibourtia demeusei, G. pellegriniana, and G. tessmannii) A much loved hardwood, perhaps among the most popular of African imports alongside species like Zebrawood and African Mahogany. In addition to its close resemblance to true rosewoods, Bubinga is also seen with a wide variety of figured grain patterns, and is sold in a wide variety of forms ranging from guitar backs to giant tabletop slabs.

True rosewoods and related species (Dalbergia spp.) While Bubinga could very well be considered every bit as popular as any rosewood, part of the weight of this listing is in its breadth. This includes all true rosewoods, worldwide, as well as a host of other venerable hardwoods found in the Dalbergia genus, such as Cocobolo, Tulipwood, Kingwood, African Blackwood, etc.

On that last point, it might seem curious to protect the entire genus, especially since there are a number of Dalbergia species out there that even the IUCN redlist classifies as being of “least concern”—Dalbergia arbutifolia, D. assamica, D.calycina, and D. cana, just to start naming a few. If this is the case, why add the entire genus to the appendices? Why such an extreme measure?

One word explains it all

At the risk of oversimplifying the problem, to boil it down to a single word to explain it all would be this: CHINA.

I’m not saying that there are a lot of other countries in the world, the United States included, that may use more than their fair share of rosewoods. But in this instance, what might be considered the “extreme” move of including the entire Dalbergia genus on the CITES appendix II, it is primarily due to what is happening in China.

While I don’t claim to even come close to having a full understanding of the culture and traditions of China, I think I have enough information to at least give a general idea of what’s happening. Long story short, Chinese people have a high regard for rosewood, and enjoy rosewood furniture. It’s part of their culture and tradition, and the wood is referred to as hongmu— which I believe literally translates as “red wood,” but is probably more accurately referred to as “rosewood.”

This “hongmu” is so highly regarded, China even has a document of standards that refers to what species are to be formally recognized as hongmu (publication no. GB/T 18107-2000). According to this document, hongmu is divided into 8 different categories, and (at the moment) includes a total of 33 species. (The list is likely to be revised and updated as new hongmu species are sought out.)

Hongmu species

Burma Padauk (Pterocarpus cambodianus, synonym of P. macrocarpus)

Andaman Padauk (Pterocarpus dalbergioides)

Kosso (Pterocarpus erinaceus)

Narra (Pterocarpus indicus)

Burma Padauk (Pterocarpus macrocarpus)

Vijayasar (Pterocarpus marsupium)

Burma Padauk (Pterocarpus pedatus, synonym of P. macrocarpus)

Huanghuali (Dalbergia odorifera)

Burmese Blackwood (Dalbergia cultrata)

Black Rosewood (Dalbergia fusca)

East Indian Rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia)

Bois de Rose (Dalbergia louvelii)

African Blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon)

Brazilian Rosewood (Dalbergia nigra)

Amazon Rosewood (Dalbergia spruceana)

Honduran Rosewood (Dalbergia stevensonii)

Ceylon Ebony (Diospyros ebenum)

Gaboon Ebony (Diospyros crassiflora)

Indonesian Ebony (Diospyros pilosanthera)

Philippine Ebony (Diospyros poncei)

Macassar Ebony (Diospyros celebica)

Kamagong (Diospyros philippensis)

Wenge (Millettia laurentii)

Thinwin (Millettia leucantha)

Pheasantwood (Cassia siamea, synonym of Senna siamea)

Looking at the above list, the most highly regarded timbers are found in categories A and C (Zitan and Huanghuali, respectively). These woods are native to areas in or near China. However, many of the woods in the secondary categories are found in Africa and Central America—suggesting that as supplies of locally-source hongmu become increasingly scarce, there is a ripple effect seen on these second-tier woods.

Referring to the actual CITES proposal that was responsible for the listing of the Dalbergia genus, the document had this to say:

Illegal logging is a prevalent problem in Central America. For instance, it was estimated in 2003 that up to 85% of the total harvest in broadleaf forests in Honduras was illegal. There is very little information on the volume of international trade although cocobolo wood is available from numerous sources online (Jenkins et al., 2012). Extensive illegal trade in rosewoods has been reported, raising concerns that it has accelerated in recent years (Jenkins et al., 2012). Seizures of illegally trafficked timber in Guatemala suggest that there is an organized smuggling ring capable of exporting large quantities. The demand for D. retusa from the Darien Region of Panama has been described as “out of control” with “hundreds of settlers looting” the species (Jenkins et al., 2012).

During the period 2011-2014, 38 shipments and vehicles, with a total amount of 906,244 m3 of Dalbergia timber (mainly trunks, flitches and tables) of D. stevensonii, D. retusa and Dalbergia spp. (reported as rosul) of illegal origin were confiscated in Guatemala (almost two times the CITES timber reported as legally exported for the same period). With the exception of two shipments destined to Honduras and El Salvador, all the other shipments were destined to Asia.

Something big is happening

So here’s the problem: Chinese rosewood furniture is all the rage at the moment. (Maybe it’s always been popular in China, but as of right now, there are starting to be a whole lot more people that can actually afford this type of furniture.)

So with over 1.3 billion people in China, and a growing percentage of middle class residents showing interest in rosewood furniture, this is an unprecedented demand. Perhaps there have been trends and fads with a higher percentage of a nation’s populace interested a certain type of wood or woodworking style, when you do the math on the sheer number of people that are showing interest in rosewood, this type of spike in demand is, to my knowledge, without rival.

So what happens when demand goes way, way up? For one thing, prices for the wood follow suit—especially as supplies dwindle. And with prices going up, people are going to be looking for all sorts of ways to get rosewood into China. With this level of money changing hands, with this level of demand, bad things are bound to happen, especially among poorer third-world countries where some of these rosewoods are naturally found.

The CITES proposal had this to say:

Hongmu trade is also linked to and drives violence in source and transit countries. In West Africa, Hongmu species are known as “blood timbers” due to connections between illegal Hongmu trade and rebel group uprisings; for example, in the Senegalese Casamance, in Côte d’Ivoire and in northern Nigeria in territories controlled by the Muslim extremist group Boko Haram. In Thailand, more than 150 forest rangers, police, soldiers and illegal loggers have been killed in gunfights during rosewood enforcement operations in recent years (EIA, 2016).

It’s quite sad that things have to come to such a point that people are dying over logs of wood. Hopefully you can see why CITES and the international community in general needed to do something. Whether or not it was the right thing, or whether it will have a measurable impact on the issue remains to be seen. But surely you can understand why some type of action was taken.

Chinese knockoffs—now including “rosewood”

So why restrict the entire Dalbergia genus, even when there are a number of species that are (according to the IUCN) clearly not endangered or even at risk for exploitation? I believe the answer is twofold.

First, given the great price of the primary rosewood species driving demand in China, knockoffs and substitutes are being sought out. This is especially true as supplies of these original timbers dwindle, necessitating the hunt for second and third tier species.

But this is also a two-way street. In addition to finding new substitute species and attempting to pass them off as the real thing, it also becomes a loophole where merchants can intentionally misidentify a (legally protected) top-tier species as a lesser (unprotected) species—thus circumventing any protective measures currently in place. The CITES proposal states:

Species shifting, as species become commercially extinct, is a common practice. For instance, with the commercial extinction of D. odorifera in China and Pterocarpus santalinus in India, the trade in D. cochinchinensis grew rapidly and it became the most sought-after Hongmu species globally (EIA, 2016). As D. cochinchinensis was overexploited the main species now dominating the Hongmu trade in South-East Asia are D. oliveri, D. bariensis, Pterocarpus macrocarpus, and P. pedatus (EIA, 2016). In 2014, an estimated 229,796 m3 of D. oliveri logs were traded internationally (EIA, 2016). More and more species of Dalbergia are entering the trade worldwide as stocks of once abundant species are being depleted.

Traffickers exploit any legal loophole to smuggle illegal timber. Traffickers have repeatedly taken advantage of the current gaps in the CITES listings, misdeclaring Dalbergia retusa as the unregulated and similar-looking Dalbergia bariensis in violation of national moratoriums and CITES listings (EIA, 2016). In Guatemala, the documents accompanying rosewood shipments often recorded the export as recycling material (such as cardboard, junk or scrap metal) or other timber species, such as Cupressus, Dialium and Miroxylum. In Mexico, D. granadillo logs are mixed with other species in ship containers to disguise the shipments from authorities since there are no permits to log this protected species (PROCESO, 2014).

Where Bubinga comes into play

A side note is that a couple of other wood types were also listed in the CITES appendix II along with rosewoods: Kosso and Bubinga. Both restrictions come almost entirely as the result of the situation in China. The CITES proposal dealing with Bubinga (listed just after the Dalbergia proposal) had this to say:

The woods of the different Bubinga species, the aesthetic qualities of which are close to those of the Asian rosewood species which are most highly prized in the Hongmu tradition, have gradually become established as the first choice alternative for this burgeoning sector. In the course of the past five years, the expansion of this “Hongmu demand” for the supply of the Chinese markets has led to unprecedented interest in Bubinga in the main producing countries of its range, particularly in Gabon and Cameroon.

So what was the fault in that Bubinga was so stringently restricted? Simply put, it looked too much like rosewood. And going right along with this, Kosso has met a similar fate. Although this species isn’t seen very often in North America, the CITES proposal commented “Available information suggest that Pterocarpus erinaceus was in 2015 the most traded species of ‘Hongmu,’ in volume, at the international level.”

Difficult wood to identify

Besides the matter of using lookalikes and substitutes, there’s also the very practical issue of reliable wood identification. If you’ve read my article on the truth behind wood identification, you’d know that reliably identifying a wood sample down to the species level is no easy task, and is in fact, short of DNA testing, at times impossible. This is not necessarily the fault of the wood anatomist or customs agent that is tasked with identifying the wood—it is inherent in the wood itself. At times, there are simply not enough unique and exclusive features present in a wood species to differentiate it from another related species. The Dalbergia genus, although chock-full of many highly unique and fabulous species, is still no exception to this identification conundrum.

The CITES proposal makes the following comment about Dalbergia species: “distinction between and identification of individual species is very difficult for non-professionals and sometimes even for experts, making it a problem for enforcement and customs officers to comply correctly with inspection and identification of CITES listed Dalbergia tree and product shipments.” Bear in mind that those writing and weighing in on this issue are some of the most knowledgeable experts in the world when it comes to wood anatomy, and even among this community, they have deemed proper identification to be “very difficult . . . sometimes even for experts”! We are talking about boiling/chemically treating a wood specimen, taking a razor thin slice of the wood, and examining the wood’s structure under a microscope. (This should hopefully be enough of an eye-opener to properly adjust one’s expectations when attempting to identify something like a guitar or other finished product simply by intuitively eyeing the face grain through several layers of wax, lacquer, stain, and pore filler.)

In a nutshell, it’s very hard to tell some of the Dalbergia species apart, and so it makes sense to simply make a blanket covering of the entire genus. Otherwise, way too many loopholes would be left open, and closely related species would be mislabeled to avoid being flagged at the border.

Big implications in the fine print

So to recap: the entire Dalbergia genus has been listed in Appendix II, along with the three species of Bubinga, as well as a Pterocarpus species (P. erinaceus) not seen too often in North America.

The rest of the story is in the annotations. If you peruse the actual CITES appendices, you may notice little numbers next to many of the wood species listed. Those are what CITES calls annotations, and it could be properly thought of as the fine print.

By default, if there are no annotations next to a species listing, then it is completely restricted, as well as all parts or derivitives of the tree—which includes finished products made from the wood. The best example is Brazilian Rosewood: its listing as “Dalbergia nigra” in appendix I has no annotation accompanying, so it, along with objects made from the wood, are restricted from international travel/shipping.

With the three wood types added for 2017, Kosso has no annotation. That means there’s no fine print, which is bad (or good, depending on your opinion of the whole matter). So in addition to the raw wood itself, even if you made a product of Kosso, in any shape or form, it can’t legally cross any national borders.

However, the remaining woods (Bubinga and Dalbergia species) are annotated with a new #15.

Annotation #15

All parts and derivatives are included, except:

a) Leaves, flowers, pollen, fruits, and seeds;

b) Non-commercial exports of a maximum total weight of 10 kg. per shipment;

c) Parts and derivatives of Dalbergia cochinchinensis, which are covered by Annotation # 4;

d) Parts and derivatives of Dalbergia spp. originating and exported from Mexico, which are covered by Annotation # 6.

So what is listed above in the annotation could be fairly considered as the exemptions (loopholes) to the new restriction. By default, everything is off the table unless exemptions are added. Letter (a) speaks of fruit, seeds, and other products from the tree itself, and is of no interest to woodworkers. Letter (b) is where things get interesting. It exempts non-commercial items that weigh less than 10 kilograms per shipment. (For those in the United States, 10 kilograms works out to roughly 22 pounds.)

I believe this clause was added with musical instruments in mind, although it could be applied to other objects made of rosewoods. Basically, as long as an item is not for sale and is simply for personal use, you can travel with it internationally. So, think of guitars made with rosewood, and other items weighing less than 22 pounds. The good news is that if you own an item made of rosewood, you should be able to travel with it without issue. But the bad news is that if you are selling any type of rosewood (either as lumber, or as a finished product), you can no longer (legally) ship it out of your country.

At this point it should be emphasized that the exemptions in annotation #15 do not apply to appendix I listed Dalbergia nigra (aka Brazilian Rosewood), which is still tightly controlled. This is only for the newly 2017-listed species added to appendix II.

Letter (c) of annotation #15 is in reference to Siamese Rosewood (Dalbergia cochinchinensis), and essentially reroutes the annotation up to #4 instead of #15 for this species. Looking at annotation #4, it is much less generous, and only exempts seeds and other tree products, so it appears that Siamese Rosewood is not eligible for the non-commercial, less than 10 kg loophole, and is shut down nearly as restrictively as Brazilian Rosewood.

Lastly, letter (d) states that rosewoods coming out of Mexico in particular are subject to annotation #6 instead of the new #15, which only restricts “Logs, sawn wood, veneer sheets and plywood.” So while raw rosewood lumber coming out of Mexico is still subject to restriction, objects made from rosewood (even those for commercial sale) are okay to transport provided that the source country for the shipment is Mexico.

Questions? Always check first

Anytime two different countries with differing cultures and languages interact, miscommunication and misunderstandings are always a possibility. This is certainly true with international shipments of wood or products as well. While I have attempted to present the most accurate and reliable information regarding the most recent changes to the CITES appendices, they should never be relied upon solely for the basis of any important international shipment.

My best advice would always be to contact the relevant governmental bodies directly and ensure that you have a clear understanding of any laws or regulations. CITES has a pretty extensive database of names and contact information that you can use to get in touch with the relevant authorities for your situation.

Are you an aspiring wood nerd?

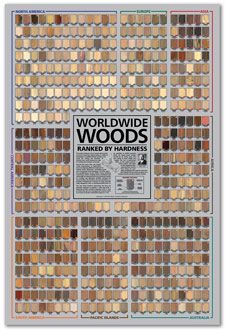

The poster, Worldwide Woods, Ranked by Hardness, should be required reading for anyone enrolled in the school of wood nerdery. I have amassed over 500 wood species on a single poster, arranged into eight major geographic regions, with each wood sorted and ranked according to its Janka hardness. Each wood has been meticulously documented and photographed, listed with its Janka hardness value (in lbf) and geographic and global hardness rankings. Consider this: the venerable Red Oak (Quercus rubra) sits at only #33 in North America and #278 worldwide for hardness! Aspiring wood nerds be advised: your syllabus may be calling for Worldwide Woods as part of your next assignment!

The poster, Worldwide Woods, Ranked by Hardness, should be required reading for anyone enrolled in the school of wood nerdery. I have amassed over 500 wood species on a single poster, arranged into eight major geographic regions, with each wood sorted and ranked according to its Janka hardness. Each wood has been meticulously documented and photographed, listed with its Janka hardness value (in lbf) and geographic and global hardness rankings. Consider this: the venerable Red Oak (Quercus rubra) sits at only #33 in North America and #278 worldwide for hardness! Aspiring wood nerds be advised: your syllabus may be calling for Worldwide Woods as part of your next assignment!

This looks like a very old article, but it is interestingly informative. May I be permitted to ask a question that is immediately relevant to me? We have a legacy furniture set (couch and two side seats) that is likely made of rosewood in India. It has been in the family for over 45 years, and my wife wants ot nring it back to the US for personal use only. Her dad passed away, and her mom has moved into a retirement home.

Would we have restrictions on import? What should we know/have as far as documentation goes?

The most annoying and counterintuitive aspect of this entire debacle, is the EUs understanding of this. Basically, every business and even every person who either sell or buy anything made with rosewoods that were logged, used and sold as finished pieces before this CITES addition, requires both the seller and the buyer to purchase a license to own the piece. It can’t be transferred or copied to the buyer and for every piece sold, a new license must be purchased. This is especially problematic for businesses that specialize in restoring and thus saving old furniture made decades ago, as it… Read more »

Another question, I’m sure many are in this situation. As hobby woodworkers – I’m sure most of us are (I was a pro but now retires). We have material in our shop that we purchased some time ago, before it was restricted, we no longer have paper work that proves it’s origin or time. Can we use this material without running into difficulty?

As far as CITES is concerned, you should be fine to own or use it. The only issue would come if you ever tried to export it to another country.

I was under the impression that the guitar manufacturers were able to get and exemption for finished musical instruments that allows finished musical instruments (that are for personal use, not for resale) can travel, regardless of what wood they are made from.

Eric, this is an excellent article. Much of the discussion below focuses on wood substitutions based on appearance for furniture and cabinetry. Tonewoods have additional requirements, and I’ve been analyzing their performance using properties from your database to create a chart that ranks the “Acoustic Radiation Coefficient” of common tonewoods that might be helpful in comparing options relative to IUCN Red List status. Might be of interest to this community.

Fascinating chart, thank you for posting and the work involved. It does put paid to much of the musical instrument industry marketing BS in many areas, but as you have already noted, there are many different measurement types. Cheers!

I think the Prop 65 was well-intentioned, but is not always useful. The fact that there was a years-long legal struggle to not require that coffee (coffee!) be listed as containing carcinogens is a good example of this sort of thing being taken too far.

I came upon your website when I was researching the Prop 65 warning on a piece of furniture I was looking to purchase. I have found it’s a very board term used by many to keep the manufacturers from a lawsuit. What are your thoughts on this Prop 65 out of California?

For further reading, I highly recommend James B. Greenberg, “Good Vibrations, Strings Attached: The Political Ecology of the Guitar,” 4 SOCIOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY 431, 431-38 (2016), https://www.hrpub.org/download/20160430/SA14-19606271.pdf If you want a substitute for ebony, there are a few options, depending on whether you use the ebony for sonic/structural purposes or decorative purposes. I have seen, used, owned, or heard of substitute uses of Sonowood, Blackwood Tek, Boxwood, and Massaranduba for sonic purposes, and you might consider dark Bog Oak if it’s color you’re after. European luthiers famously made the black parts of their purfling by staining pear wood black with… Read more »

Does this mean that pieces of indian rosewood can be imported as long as they weigh fewer than 10 kg? If so, that would still be enough to supply small luthier shops with all of this wood that they need. The wood for guitar backs/sides is thin enough to not weigh very much. If I’m missing something on this, please fill me in.

No, they can’t. What you’re missing is that the 10kg loophole only exists for finished products (such as guitars), and not for raw wood.

I wonder what would be the legality of selling finished serving trays that happen to be about the size of acoustic guitar back and sides and then repurposing them once imported.

It’s called circumvention. It’s not legal and you will 1) pay a fine, 2) get your stuff detained by customs officials, and 3) be liable for a comfy stay a federal facility.

Some inaccurate information here, as compared to what I gather from the documents I’ve read: — CITES is not voluntary, at least not as far as its effect on individuals. It is an international treaty ratified by 182 countries, who have all agreed to implement laws and regulations in their countries to support CITES agreements. In contrast, FSC is an advocacy / marketing group. — Appendix II listing is *not* a ban. As the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said in a 2016 letter published when the listings for these species were about to go into effect, “The Appendix-II listings… Read more »

I’m not sure all the exact criteria that’s used to determine eligibility, but the CITES appendices explicitly state the exemption applies only to “finished products.” (See attachment taken from current appendices.)

Ah, yes, the language in the 2016 Fish and Wildlife Service letter was sloppy (it can be found at https://web.archive.org/web/20220120180640/https://www.fws.gov/international/pdf/letter-appendix-III-timber-listings-november-2016.pdf). The current USDA Timber Manual also specifies finished products. So if someone in Canada pops across the border and buys a pen turning blank at a woodworking store, they couldn’t bring it home with them. :(

The cross border shipping paperwork issue makes no sense to me. Rosewood does not grow in the U.S. so it needs paperwork to satisfy cites to come into the U.S. Why wouldn’t the same paperwork be good enough to go with the wood if sent on to another country out of the U.S. Part of the problem with Cites is that every country decides how it will be applied and enforced in that country. In Canada for instance it is Environment Canada. I have contacted them several times with cites questions and they never reply. I am a “hobby” guitar… Read more »

With respect Bob, getting any kind of useful answer out of any department of the government of Canada is a serious challenge

and if you do, get it in OFFICIAL WRITING.

Well a Priceless Brazilian 150-200yr old Pre-Beetle Reclaimed Rosewood Kitchen Table from Hamburg Germany(family) to my Homes on the eastern seaboard of US isn’t leaving the Country & not for sale even an $13,000 offer appeared(just for the Top Piece alone…… thanks for the info I now know why & where it was going….???????

What paper work is needed to make a sale legal? Why are resellers restricting sale, for instance; US sellers of East Indian rosewood guitar back and side sets are not shipping out of the country? If there is paper work to move the rosewood from India to the US, why can’t that paper work just go with the wood to the next destination?

The exemption only covers finished products made of the wood, so that would exclude back and side sets. It was created to protect pre-existing guitars and other musical instruments.

So, if rosewoods are banned for import/export does that also apply to people travelling to and from different countries with their personal musical instruments?

They actually added an exemption after this resolution was passed, which made exceptions for finished products that weigh under 10 kilograms (about 22 lbs). So this had the effect of allowing most instruments through, but stopping larger pieces like furniture.

Fantastic article Eric. Great work! Really highlights the confusion when it comes to timber & the governance / regulation of it. Couple of questions Eric that I’ll try to keep brief.

Thanks.

Paul.

1. I don’t know for sure. “Regulatory power” can be very subjective, and technically the FSC is a non-profit, so it has as much authority as individual national governments will give it. Likewise, CITES is a voluntary, opt-in entity for all nations involved. 2. They are “banned” only in the sense that they cannot cross international borders without scrutiny. 3. Possibly pre-existing stock? Also note that most online retailers will now note that CITES species “can’t be shipped internationally” — so regardless of how the wood entered the country, the public-facing side of any dealer should reflect this restriction. Also… Read more »

Great article and super-interesting (if disturbing) topic. If the import of these woods has been banned for years now, why do I still see cocobolo, ebony, bubinga, etc. available for sale in the US? Did we really have that much domestic stock built up? Getting smuggled in anyway? Fakes? Anyone have any thoughts on this? Just curious.

Could be the stocks of these woods were obtained prior to CITIES listing. I have many woods in small form (hand spindles) that I have purchased from a well known woodworker in the spinning world. I’m sure he’s legit so I am also sure his stock was obtained prior to listing. In fact, I have at least 13 wood spindles that would be considered banned now. Of course my individual spindles are not of much weight, point being that he had obtained sufficient supply for his business, and must have been prior to the CITIES ban. What I own in… Read more »

So can you grow it and sell it in the US? No export taking place.

Yes

I wonder why there isn’t more of it planted if it’s legal. Invasive species? Not profitable because the majority of demand is in China and it cannot be exported? Just seems like if it’s such an important issue that peoplew would be growing it

I think it mostly comes down to money. Most of these woods are endangered for a reason, they aren’t easily sustainable, and are slow growing. After you crunch the numbers, let’s say hypothetically you discover that you’d be making double the money by growing pine instead of rosewood. It becomes hard to justify it if it’s done on a large scale for profit.

Dunno if i’d call the Chinese a species of their own. Invasive I’ll give you. To answer your question with a question: if so much of the demand is in China and it can be grown elsewhere, why isn’t CHINA planting massive forests of the stuff? It’s all a numbers game. Trees grow slower than people. And we have a LOT more people inbound. Last study I read speculates we need to increase worldwide food production 70 PERCENT by 2050 just to MAINTAIN the 11% famine/starvation rate the world “enjoys” right now. But one can grow bushels and bushels of… Read more »

They are growing dalbergia nigra in south Florida .

How far south? I am between 27 and 28 Lat

What if it is a 19th century desk for example made in Brazilian rosewood. Can it be imported to the US from Europe for example?

The revised CITES Appendices come into effect on 26 November

On August 29, 2019, CITES announced that the parties (countries) have agreed to make an exception for musical instruments. When this will be effective, I don’t know.

https://www.cites.org/eng/CITES_CoP18_moves_towards_strengthened_regulations_for_tropical_trees_as_well_as_cautions_exemptions_for_rosewood_musical%20_nstruments_29082019

Fascinating article. I’d like to know what happens to the illegal shipments of timber when they’re seized/confiscated. It’s not as if they can be re-planted is it!

in Belize, they burn them

same as with elephant ivory, it dwindles supply and drives up prices :(

so I’d better NOT take my cocobolo ukulele to England & Ireland it seems

Scary. I definitely want to do the right thing and don’t ever want to have anything to do with exhausting or making extinct any kind of wood. That said, I have an old circa 1966 Martin D-12-35 guitar with Brazilian rosewood sides and back that I bought from a guy used around 1975. I would hope and expect that the serial number and obviously old nature of the guitar itself *should* provide sufficient evidence that the guitar was made long before any law went into effect prohibiting that wood from being bought or sold or moved across borders. But I… Read more »

One day there will be no timber (lumber) of large enough size (trees) for worthwhile trade. cites at that time if still in existence will be no more than a tree seed trading body !

Keep it before there is non.

One wood I have used a lot of is Dalbergia sissoo.It is very common in Florida.It should actually be planted for harvest in years to come.

It is a very fast growing tree.an inch a year.I talked to a guy that planted 3 and he moved there 36 years before and at 4 feet they were 36 inches.

Keeps the price of wood artificially high because there is no cross border arbitrage.

Although I agree with some kind of control this is bananas, A huge organization has been formed.

Who pays those salaries? Its more about control than protecting woods. Why would a professional musician be penalized for wood crimes committed by a tree decades ago when one of the Major parties to this U.S.A. do not even recognize global warming which will call all the trees eventually. Its all about the money.

ou answered your own question. Price Control. Its the same two parties in this U.S.A. that play the global warming game in order for the politicians of said parties can grift off the citizens taxes.

I make custom made pens. I’m curious if shipping the pens across borders is restricted. I live in the US. I have Bubinga, and some form of Rosewoods. Other exotics also. I’ll be looking up the CITES appendices to see what is actually listed. These woods were bought online and there was no “When we run out of this stock it will be discontinued” warning. So…Are the woods I was sent NOT what they claimed?

Fascinating! I am considering buying a marimba and was researching the difference between padauk and rosewood. And now – holy cow! Which should I buy? Rosewood is expensive, but it might be a good investment since it may not be available in the future. Or a horrible investment because I might not be able to sell it. Padauk sounds like a more responsible way to go. Would love to get your opinion.

I don’t think you’d have any problems selling it unless you live in a fairly small country where you would not be able to find a local buyer. Given the two options, you are probably right that the padauk is the more responsible option.

I would stay away from padauk if there is an alternative. Padauk looks beautiful when freshly finished but the color fades over time (not even a very long time). It turns into something that’s almost indistinguishable from walnut.

I am feeling myself a rich man. From all the at the poster pictured Rosewoods and many more, I have good quality wood samples in many different grain patterns and colors in my more then 15000 wood samples large wood collection.

I’m trying to identify which species Sangualica belongs to. The trees and its wood are from Michoacan, Mexico (and very few other places in Central America). I believe it is in the Delbergia family. If so, I’m sure its banned in Appendix I. I’m also looking to identify a wood that a Michoacan local has called Coral and also included the name Guacamayo to a sample given to me. My problem is that the two name do not relate to each other, but I did find coral as within the Erythrina family.When sanded the wood is more white but the… Read more »

In the past several years I’ve had many opportunities to shop local markets in Thailand, and I have seen some very beautiful small pieces of wood. In researching the wood, I determined it to be Siamese Rosewood, and, at the same time, learned that it was on the Cites banned list even back then. I also learned the main reason for it being banned. From the very beginning of Eric’s video, all I could think of was Siamese Rosewood and why it is banned, and then, he said it. The one word I was waiting to hear… China! The primary… Read more »

You are not alone of being sick of how dishonest merchants selling fake and using sapwood to mixed into the Hongmu furniture. The Hongmu furniture business has always been a dark trading business – meaning if one does not has knowledge of Hongmu information in how to distinguish the different species of woods ( one would be sold with the fake Hongmu). There were so many Hong Kong people also brought fake rosewood furniture. Before China took over Hong Kong in 1997, it is true that during that period Hongmu furniture were mostly exported to Hong Kong and North America.… Read more »

Great write up about CITES and Rosewood. I liked the artile so I ordered the Wood! book.

As far as I’m aware, CITES Appendix II species can still be traded / exported / imported legally, as long as you apply for an export or re-export permit from the relevant authorities for your country. However, many timber merchants have said that once their current stocks of a particular species have run out, they will no longer be supplying the wood due to the extra hassle and cost of applying for permits, so these species will become a lot more difficult to obtain in the near future.

I understand these regulations relate to commercial entities, i.e. those that earn money from sale and resale of these woods. But what about your average Joe woodworker? What if someone doesn’t have a corporation set up? Do these regs still apply? And lastly, are these international laws, or just policies, or what? What power of enforcement do they actually have to an American citizen? As such, I am not subject to international law, only American law.

They only apply to international trade! hence the acronym. This article is very misleading on that topic. The only case a US business or person would need permits would be to directly import listed species or export goods in excess of or outside of exempted quantities and or forms. The Lacy Act (a US anti-poaching law from the 1800’s, expanded under the Bush W. administration) is another beast altogether, and it’s scope is ridiculously broad and almost certainly unconstitutional as written. Those enforcing it have so far only gone after companies that knowingly imported illegally harvested woods from another country,… Read more »

Excuse me EVERYONE is subject to international law.

Not if you don’t cross borders. If you remain in the US you are only subject to US law.

Not sure if you read the whole article above or not, but I believe most of your questions and concerns have already been covered. From the article, under the heading “What in the world is going on here?” “It all starts with an organization called CITES, which stands for Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. The keyword here is *international* trade. This new development has impact only for wood that is crossing international borders. If you’ve got wood in your shop, you’re cool—nothing to worry about. But before you write this latest development off as nothing of note, you… Read more »

It ONLY relates to crossing borders (i.e., SHIPPING & TRAVEL)

You can still do whatever with existing stocks within the borders of whatever country they are in.

Though it *is* maddening that there is no blanket international air travel exemption on personal luggage. Or finished items clearly old/antique

China has a long history of using Hongmu (rosewood) since Ming Dynasty, the precious rosewoods were only allowed to be used by King and Nobles in making of furniture. The major reason Chinese are so much into rosewood furniture is that it has a capability of appreciation in value. The other reason is that the furniture itself will last for thousand years. The chosen 33 spices as China Hongmu was under heavy research and the Hongmu required at least hundreds of years to grow in order to be able to use for furniture making. Since some of the best rosewood… Read more »

I was involved in listing wood species on CITES back in the 1990s BRW ,big leaf mahogany and a few others and was the CITES liaison for the good wood alliance back in the day. Nice info here but you are missing a fundamental point Appendix ll is Not A Ban!! Countries can still export so long as the harvest is deemed to be non-detrimental to the survival of the species. Ap. ll species can be exported with a permit and is meant to stop illegally harvested wood from being sold on the international market. from the CITES website: Appendix… Read more »

Thank you for explaining this. Do you have any suggestions for an alternative to rosewood?

The simplest alternative that I can suggest is to use dark colored woods that are native to your country. So for those in the United States, if done well, black walnut can look really nice.

I understand everything you said about Rosewood being banned, but what happens if a musician travels to gigs abroad and has say, a 1942 Martin D28 made with Brazilian Rosewood. Surely the fact that the instrument was made 70yrs ago should exempt it from these regulations?

It is possible to get a “passport” for your Brazilian Rosewood guitar, as long as you can prove that the instrument was made before 1992. More info available in this video on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGNXeifmYBo&t=318s

I wouldn’t risk it, “passport” or no. Remember that you’re relying not on the laws and regulations themselves, but on the ability of customs/TSA/border control agents to understand and care about your situation and be up to date and clear on the regulations. There is no guarantee they will do so, and ample evidence that the contrary is likely.

Unless you’re moving, I would leave that guitar at home – it isn’t worth the risk of losing something irreplaceable, and virtually no listener at a live venue could possibly tell the difference, anyway.

Because this law is SO badly worded, your best move if you absolutely gotta would be a BS document for a much newer but similar looking Martin guitar that uses less restricted woods.

Or better yet, travel with a cheapie piece of junk, not a valuable vintage collectible. Keep relevant papers for the acoustics, and consider sticking to maple fretboards on electrics used on international tours.

Thanks so much. This was very helpful. I’m currently making something from an old piece of Brazilian or indian rosewood that my father gave me. Looks like that’ll be the last of that. You might try comparing these exotic and exploited woods to ivory when you talk about them. They are beautiful, but are they worth the cost? I had no idea there was a potential link to Boko Haram and such. But harvesting of any valuable resource seems to inevitably lead to organized crime, and now potentially terrorists. Maybe we just need to get used to walnut. Though friends… Read more »

These woods from northern Nigeria is not in any way connected to boko haram, this is what i know as a supplier

Great video, well written article. I appreciate the effort.

If the issue that caused the blanket listing is the difficulty in telling the woods of the various Dalbergia spp. apart, then why the exception for Mexican finished goods? Doesn’t that just put everything back where it started?