by Eric Meier

When attempting to identify a wood sample, it’s important to keep in mind the limitations and obstacles that are present in our task. Before starting, please have a look at The Truth Behind Wood Identification to approach the task in a proper mindset; I consider the linked article to be required reading for all those visiting my site with the intent of identifying wood.

1. Confirm it is actually solid wood.

Before proceeding too much farther into the remaining steps, it’s first necessary to confirm that the material in question is actually a solid piece of wood, and not a man-made composite or piece of plastic made to imitate wood.

Can you see the end-grain?

Manufactured wood such as MDF, OSB, and particleboard all have a distinct look that is—in nearly all cases—easily distinguishable from the endgrain of real wood. Look for growth rings—formed by the yearly growth of a tree—which will be a dead-giveaway that the wood sample in question is a solid, genuine chunk of wood taken from a tree.

Is it veneered?

If you see a large panel that has a repeating grain pattern, it may be a veneer. In such cases, a very thin layer of real wood is peeled from a tree and attached to a substrate; sometimes the veneer can be one continuous repeating piece because it is rotary-sliced to shave off the veneer layer as the tree trunk is spun by machines. Assuming it is a real wood veneer with a distinct grain and texture—and not merely a piece of printed plastic—you may still be able to identify the outer veneer wood in question, but you should still realize that is it only a veneer and not a solid piece of wood.

Is it painted or printed to look like wood?

Many times, especially on medium to large-sized flat panels for furniture, a piece of particleboard or MDF is either laminated with a piece of wood-colored plastic, or simply painted to look like wood grain. Many of today’s interior hardwood flooring planks are good examples of these pseudo-wood products: they are essentially a man-made material made of sawdust, glues, resins, and durable plastics.

2. Look at the color.

Some questions to immediately ask yourself:

Is the color of the wood natural, or is it stained?

If there is even a chance that the color isn’t natural, the odds are increased that the entire effort of identifying the wood will be in vain.

Is it weathered or have a patina?

Many woods, when left outside in the elements, tend to turn a bland gray color. Also, even interior wood also takes on a patina as it ages: some woods get darker, or redder, and some even get lighter or lose their color; but for the most part, wood tends to darken with age.

Is it possible to sand or plane the board to see the natural raw color of the wood?

The most predictable baseline to use when identifying wood is in a freshly sanded state. This eliminates the chances of a stain or natural aging skewing the color diagnosis of the wood.

3. Observe the wood grain.

If the wood is unfinished, then look at the texture of the grain. Ask yourself these questions:

Does the wood have an open, porous texture?

Most softwoods will be almost perfectly smooth with no grain indentations, while many common hardwoods have an open pore structure, such as oak or mahogany; though there are some hardwoods that are also smooth to the touch, such as maple.

Can you tell if the wood is quartersawn or plainsawn?

By observing the grain patterns, many times you can tell how the board was cut from the tree. Some wood species have dramatically different grain patterns from plainsawn to quartersawn surfaces. For instance, on their quartersawn surfaces, lacewood has large lace patterns, oak has flecks, and maple has the characteristic “butcher block” appearance.

Is there any figure or unusual characteristics, such as sapwood, curly or wild grain, burl/knots, etc.?

Some species of wood have figure that is much more common than in other species: for example, curly figure is fairly common in soft maple, and the curls are usually well-pronounced and close together. Yet when birch or cherry has a curly grain, it is more often much less pronounced, and the curls are spaced farther apart.

4. Consider the weight and hardness of the wood.

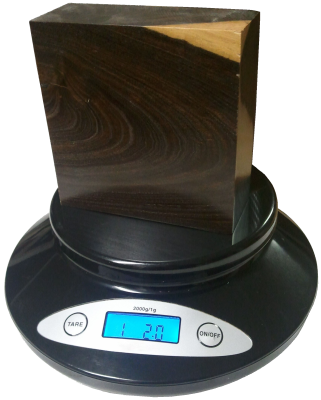

If it’s possible, pick the piece of wood up and get a sense of its weight, and compare it to other known wood species. Try gouging the edge with your fingernail to get a sense of its hardness. If you have a scale, you can take measurements of the length, width, and thickness of the wood, and combine them to find the density of the wood. This can be helpful to compare to other density readings found in the database. When examining the wood in question, compare it to other known wood species, and ask yourself these questions:

Is the wood dry?

Wood from freshly felled trees, or wood that has been stored in an extremely humid environment will have very high moisture contents. In some freshly sawn pieces, moisture could account for over half of the wood’s total weight! Likewise, wood that has been stored in extremely dry conditions of less than 25% relative humidity will most likely feel lighter than average.

How does the wood’s weight compare to other species?

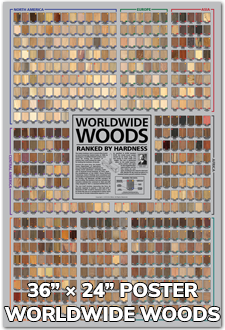

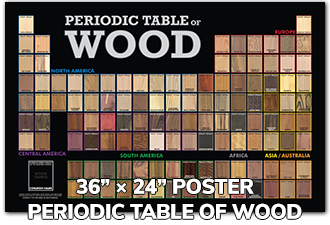

Taking into account the size of the board, how does its weight compare to other benchmark woods? Is it heavier than oak? Is it lighter than pine? Look at the weight numbers for a few wood species that are close to yours, and get a ballpark estimate of its weight.

How hard is the wood?

Obviously softwoods will tend to be softer than hardwoods, but try to get a sense of how it compares to other known woods. Density and hardness are closely related, so if the wood is heavy, it will most likely be hard too. If the wood is a part of a finished item that you can’t adequately weigh, you might be able to test the hardness by gouging it in an inconspicuous area. Also, if it is used in a piece of furniture, such as a tabletop, a general idea of its hardness can be assessed by the number and depth of the gouges/dings in the piece given its age and use. A tabletop made of pine will have much deeper dents than a tabletop made of Oak. Additionally, you can always try the “fingernail test” as a rough hardness indicator: find a crisp edge of the wood, and with your fingernail try to push in as hard as you can and see if you’re able to make a dent in the wood.

5. Consider its history.

Many times we forget common sense and logic when attempting to identify wood. If you’ve got a piece of Amish furniture from Pennsylvania, chances are more likely that the wood will be made of something like black walnut or cherry, and not African wenge or jatoba. You might call it “wood profiling,” but sometimes it can pay to be a little prejudiced when it comes to wood identification. Some common-sense questions to ask yourself when trying to identify a piece of wood:

Where did it come from?

Knowing as much as you can about the source of the wood—even the smallest details—can be helpful. If the wood came from a wood pile or a lumber mill where all the pieces were from trees processed locally, then the potential species are immediately limited. If the wood came from a builder of antique furniture, or a boat-builder, or a trim carpenter: each of these occupations will tend to use certain species of woods much more often than others, making a logical guess much simpler.

How old is it?

As with the wood’s source, its age will also help in identification purposes. Not only will it help to determine if the wood should have developed a natural patina, but it will also suggest certain species which were more prevalent at different times in history. For instance, many acoustic guitars made before the 1990s have featured Brazilian rosewood backs/sides, yet due to CITES restrictions placed upon that species, East Indian rosewood became a much more common species on newer guitars. (And this is a continuing shift as newer replacements are sought for rosewoods altogether.)

How large is the piece of wood?

Some species of trees are typically very small—some are even considered shrubs—while others get quite large. For instance, if you see a large panel or section of wood that’s entirely black, chances are it’s either painted, dyed, or stained: Gaboon ebony and related species are typically very small and very expensive.

What is the wood’s intended use?

Simply knowing what the wood was intended for—when considered in conjunction with where it came from and how old it is—can give you many clues to help identify it. In some applications, certain wood species are used much more frequently than others, so that you can make an educated guess as to the species of the wood based upon the application where it was used. For instance, in the United States: many older houses with solid hardwood floors have commonly used either red oak or hard maple; many antique furniture pieces have featured quartersawn white oak; many violins have spruce tops; many closet items used aromatic red cedar, and so forth. While it’s not a 100% guarantee, “profiling” the wood in question will help reduce the number of possible suspects, and aid in deducing the correct species.

6. Find the X-Factor.

Sometimes, after all the normal characteristics of a sample have been considered, the identity of the wood in question is still not apparent. In these instances—particularly in situations where a sample has been narrowed down to only a few possible remaining choices—it’s sometimes helpful to bring in specialized tests and other narrower means of identification.

The following techniques and recommendations don’t necessarily have a wide application in initially sorting out wood species and eliminating large swaths of wood species, but will most likely be of use only as a final step in special identification circumstances.

Odor

Believe it or not, freshly machined wood can have a very identifiable scent. When your eyes and hands can’t quite get a definitive answer, sometimes your nose can. Assuming there is no stain, finish, or preservative on or in the wood, quickly sand, saw, or otherwise machine a section of the wood in question, and take a whiff of the aroma.

Although new scents can be very difficult to express in words, many times the scent of an unknown wood may be similar to other known scents. For instance, rosewoods (Dalbergia spp.) are so named for their characteristic odor that is reminiscent of roses. Although difficult to directly communicate, with enough firsthand experience scents can become a memorable and powerful means of wood identification.

Fluorescence

While certain woods can appear basically identical to one another under normal lighting conditions, when exposed to certain wavelengths—such as those found in blacklights—the wood will absorb and emit light in a different (visible) wavelength. This phenomenon is known as fluorescence, and certain woods can be distinguished by the presence or absence of their fluorescent qualities. See the article Fluorescence: A Secret Weapon in Wood Identification for more information.

Chemical Testing

There are only a small number of chemical tests regularly used on wood, most of which are very specialized and were developed to help distinguish easily confused species with one another. They work by detecting differences in the composition of heartwood extractives. A chemical substance (called a reagent) is usually dissolved in water and applied to the wood surface: the surface is then observed for any type of chemical reaction (and accompanying color change) that may occur. Two of the most useful are the tests that are meant to separate Red and White Oak, and Red and Hard Maple.

Heartwood Extractives Leachability

Sometimes a wood species will have heartwood extractives that will be readily leachable in water and capable of conspicuously tinting a solution of water a specific color. For instance, the heartwood extractives contained in osage orange (Maclura pomifera) contain a yellowish-brown dye that is soluble in water. (This can sometimes be observed anecdotally when the wood is glued with a water-based adhesive: the glue’s squeeze-out is an unusually vibrant yellow.)

In a simple water extract color test, wood shavings are mixed with water in a vial, test tube, or other suitably small container, and the color of the water is observed after a few minutes. If the heartwood extractives are leachable by water, then a corresponding color change should quickly occur.

In addition to osage orange (Maclura pomifera), merbau (Intsia spp.), and rengas (Gluta spp. and Melanorrhoea spp.) are also noted for their readily leachable heartwood extractives. Because this property is quite uncommon, it can serve to quickly differentiate these woods from other lookalikes.

7. Look at the endgrain.

Perhaps no other technique for accurate identification of wood is as helpful and conclusive as the magnified examination of the endgrain. Frequently, it brings the identification process from a mostly intuitive, unscientific process into a predictable, repeatable, and reliable procedure.

Looking at the endgrain with a magnifier shouldn’t be a mystifying or esoteric art. In many cases, it’s nearly as simple as examining small newsprint under a magnifying glass. There are three components necessary to reap the full benefits contained in the endgrain:

I. A prepared surface.

When working with wood in most capacities, it becomes quickly apparent that endgrain surfaces are not nearly as cooperative or as easily worked as face grain surfaces. However, in this case, it is absolutely critical that a clear and refined endgrain surface is obtained.

For a quick glance of a softwood sample, a very sharp knife or razor blade can be used to take a fresh slice from the endgrain. However, in many denser species, especially in tropical hardwoods, one of the best ways to obtain a clear endgrain view is through diligent sanding. It’s usually best to begin with a relatively smooth saw cut (as from a fine-toothed miter saw blade) and proceed through the grits, starting at around 100, and working up to at least 220 or 320 grit, preferably higher for the cleanest view.

II. The right magnifier.

It need not be expensive, but whatever tool is used to view the endgrain should have adequate magnifying power. In most instances, 10x magnification is ideal, however, anything within the range of 8 to 15x magnification should be suitable for endgrain viewing. (Standard magnifying glasses are typically in the range of 2 to 4x magnification.)

These stronger magnifiers, sometimes called loupes, usually have a smaller viewing area than standard magnifying glasses. Fancier models—with built in lights, or larger viewing surfaces—are available at a premium; but the most basic models are usually only a few dollars.

III. A trained eye.

The third element that constitutes a proper endgrain examination is simply knowing what to look for. In analyzing the patterns, colors, shapes, and spacing of the various anatomical features, there is a veritable storehouse of information within the endgrain—all waiting to be unlocked. Yet, if these elements have not been pointed out and learned, the array of features will simply seem like an unintelligible jumble. The discipline of recognizing anatomical endgrain features is not easily summed up in a few sentences or even a few paragraphs, but it is nonetheless critical to the identification process. To this end, an in-depth look should be given to the various categories, divisions, and elements that constitute endgrain wood identification on the macroscopic level. (In this regard, macroscopic denotes what can be seen with a low-powered, 10x hand lens—without the aid of a microscope—rather than simply what can be seen with the naked eye.) Because the anatomy between softwoods and hardwoods is so divergent, each will be considered and examined separately:Still stumped?

If you have a mysterious piece of wood that you’d like identified, you’ve got a few options for next steps:USDA’s Forest Products Laboratory

You can mail your physical wood samples to the Center for Wood Anatomy Research.

Pros:

- Free

- Professional wood identification

Cons:

- Only available to US citizens

- Slow turnaround times (up to a month or more)

- Limited to three IDs per year

See their Wood ID Factsheet for more info.

Alden Identification Service

You can mail your physical wood samples (even small sections taken from antiques) to Alden Identification Service.

Pros:

- Professional wood identification

- Faster turnaround times (ranging from a few days to a week or two)

Cons:

- Paid service

See their ordering page for more info. (Note that Harry Alden has written several books while at USDA, including both Hardwoods and Softwoods of North America.)

Ask for help online

If the wood ID is merely a curiosity, or non-critical, you can post pictures of the wood in question.

Pros:

- Free

- No need to send physical samples

Cons:

- Greatly limited by the quality of the pictures provided

- Extra work usually required to get adequate clarity in photos

See article of Common US Hardwoods to help find the most commonly used woods.

Get the hard copy

If you’re interested in getting all that makes The Wood Database unique distilled into a single, real-world resource, there’s the book that’s based on the website—the Amazon.com best-seller, WOOD! Identifying and Using Hundreds of Woods Worldwide. It contains many of the most popular articles found on this website, as well as hundreds of wood profiles—laid out with the same clarity and convenience of the website—packaged in a shop-friendly hardcover book.

If you’re interested in getting all that makes The Wood Database unique distilled into a single, real-world resource, there’s the book that’s based on the website—the Amazon.com best-seller, WOOD! Identifying and Using Hundreds of Woods Worldwide. It contains many of the most popular articles found on this website, as well as hundreds of wood profiles—laid out with the same clarity and convenience of the website—packaged in a shop-friendly hardcover book.

Why I will no longer be replying to every wood ID request I’ve replied to literally thousands of wood ID requests on this site over the past 13+ years, but as the site’s popularity has grown, so has the time demands for ID on a daily basis. (Contrary to what some may seem to think, I am not some all-knowing wood wizard that can instantly ID your wood. It can actually take me a long time to sift through a lot of different resources.) Over the past few years, my backlog of pending wood species to be added to the… Read more »

Here is the end grain, it wouldn’t let me upload both in one comment

Hi my grandfather used to make beautiful handmade furniture before he passed. I found these boards in his shop. I do a lot of wood carving and make hand carved necklace pendants as well. If anyone could tell me what type of wood these are it would be great. I know he used alot of cherry I suspect the one on the left to be that but am unsure. I put feed and wax(orange oil and beeswax) on a small area of each. I would like to turn these into something beautiful but would really like to know the wood… Read more »

Given that it’s probably fairly old stock, my best educated guess among commonly used domestic and imported hardwoods would be mahogany. The color of the wetted wood is pretty dark, but not out of the question for older pieces of mahogany. Seeing a closeup picture of the endgrain might help to ID it with more certainty.

Can you tell me what this wood is? Picture attached. House is 5 years old. Thanks for any help!

My first instinct would be to say some type of softwood like pine, but in the upper left where the light hits the wood, it appears that the darker growth ring area is eroded (presumably by some artificial weathering/distressing technique), which would suggest a ring-porous hardwood, possibly ash. In softwoods, the darker part of the growth ring is actually harder than the lighter part (opposite is true for stained hardwoods), so it wouldn’t be the section to be eroded.

The top of this table was sold to me as 40yr air dried walnut (in 4×11″ beams). After a couple unsuccessful refinishes to mute the red, I’m wondering if it’s the air drying that caused it to color this way, or if it’s actually another species (maybe claro but something just seems off). It’s hard and heavy as hell, some sapwood retention in the beams before resaw and trimming showed stark white contrast. Any ideas? I read somewhere that sometimes red gum (?) is mistaken for/sold as walnut to the unknowing. Thanks!

Can you get a closer picture of the grain? Can’t tell from that distance.

Hi! Any chance you can identify this type of wood? I bought it sight unseen and all I know is that it’s a mid century “wood” dining table. I can’t tell if it’s veneer or solid. Thanks!

Can you get a closer picture of the grain? Can’t tell from that distance.

Hi! Here is a closer crop of the middle of the six foot table. Any help would be great. Thanks so much!!

Those nearly perfectly repeating patterns would strongly suggest a veneer. As for the wood species, I still can’t tell from that distance, but at the very least the color and grain resemble rosewood — whether that is because it actually is rosewood, or simply stained to look that way, I can’t say for sure.

Thank you! You’re the best! I finally heard back from the seller and it is indeed veneer rosewood. You’re amazing at this.

Any help identifying would be great, came from posts of a barbwire fence

I removed, basically no rot at the base, I tear out a bunch of really old cedar that rots slow but nothing like these, sawdust when cut or sanded it really yellow. Really hard and heavy

I’m going to guess osage orange

Sinker Cypress?

Thanks for providing this forum to further our education about wood! I have a piece of wood that I have saved for almost ten years for a “Special Project” but I want to get more and the source I got this piece from is no longer available. All I was told is that it’s considered “Ironwood”, nothing more. Very tight grain (see end grain in the photo) and very heavy (15.1oz or 425.5 grams) for it’s size (1.5”x1.5”x10.625” or 3.8cmx3.8cmx27cm). Photo is attached. Can anyone possibly identify what species by common name? Many thanks in advance.

Partially sanded down the piece to try to match the wood. Any help would be great.

Please help identify. I think it’s cherry. It’s very heavy and dense with reddish and grayish areas in the wood. I pulled it from an old shipping crate and planed it down. Thanks.

I have the same wood I think it’s cherry but I don’t really know. I’ve never seen herry like that I have about 2 or 3 trees like this. I build furniture and I find 7 or 8 cherry trees pushed over by the stars to wilden the road.

Hi Eric, I read through your guide and found it thoroughly helpful but in this circumstance I was unable to reach a confident conclusion. The door is from Indiana, though I am not sure if the wood originated there. Sorry for my ignorance. What is your opinion on it?

What type of wood? It’s kitchen cabinets.

Looks like stained oak to me. Those little black spots are made with a technique called flyspecking, which was popular in the 70s and 80s…

What type of wood are my kitchen cabinets? they appear to be oak, but I am not sure. Also, does anyone know the color that you would call them? Is it a white wash? There is an odd color tint to them.

Can you get a closer shot of the grain? The image looks a little washed out from that distance.

Anyone know what this wood is?

Pretty tough to ID with a grain that is so bland. Might have better luck with ID getting a very close pic of the endgrain once it’s been sanded to a fine grit for clarity.

Pecan

What type of wood is this have used tree guides and can’t figure it out

Thanks

This is a hall tree coat rack from, I think, early 1900s. When stripped down, the wood was reddish. Do you know what kind of wood it is?

Looks like a type of mahogany to me.

A deep, rich mahogany.

Help please, Eric or anyone who has an idea what this timber is. I`m in Bristol, UK. This piece is one of 3 boards, the one in the pic is 38″ long x 16″ wide x 1/2″ thick. The end grain pic shows light sanding. The other 2 boards are 2 metres long x 38″ wide x 1/2″ thick. The boards were originally owned by an old neighbour 40 years ago whose hobby was making clock cases, but never used them. They were given to me but until now I never had a use for them. The boards have been… Read more »

Does anyone know what type of wood this is?

want to purchase this table but not sure what type of wood has these knots and grain patterns

Hi, does anyone know what kind of wood this is? Thanks!

Possibly maple?

I cannot figure out what type of wood this is. It was a part of a teak table around the teak slats. I know for a fact the slats are teak but I’m not sure this is.

The one in the middle reminds me of walnut, but these pieces look strange, especially that brown heartwood splotch in the lower right corner of the picture.

Can someone identify this for me? It’s very hard and very heavy. It’s from a dead tree from my backyard here in Central Texas. I have enough to make a few bar stools that I thought would be kind of cool. Thank you

Purchased this old dresser and when I sanded off the stain I could not identify this wood? Anyone know?

Hello,

Can anyone tell me the species of this wood please?

A fair amount of it fell off a ship and washed ashore 16 years ago. (In Wales, UK)

Thanks.

This is a sample of a veneer from a 65 year old cedar chest. There are some areas chipped that I would like to fix, just not sure what the wood type is. Chest was made by Cavalier in Chattanooga, TN. Any help would be appreciated.

Was able to identify the wood, it’s Tornillo

Any ideas what this sideboard is made from?

Wondering what this desk is made of. Any idea? I am trying to sell it but it makes it tough to get what it’s worth without knowing what kind of wood. Any help would be great. Thanks.

Can’t tell from that distance, is it possible to get a closer image?

I have been repairing this tool box which was made about 60 years ago. I need to replace the lid top, which was made using a laminate, rather than a solid wood.

What type of wood do you think this is? Or what wood would give me a close match.

The attached piture shows the box after i applied a bees wax finish.

Thanks in advance

Chris

Best guess and probably best match would be to try and find some type of mahogany with a grain and color that comes close to your existing piece. https://www.wood-database.com/wood-articles/mahogany-mixups-the-lowdown/

Hello Eric,

I recycled this wood from pallets and it smells like the small engraved statues that arrive from Africa and India.

Thanks a lot,

Luigi, Italy

What type of wood is this? It’s solid wood just not sure the type. I was told red oak but don’t think it is

Hello. I purchased a lot of this old barn wood to use on the ceiling of my cabin. It would be fun to identify the species of the wood. It came from an old farm in Nebraska and is estimated to be about 100 to 150 years old. Any assistance would be appreciated! Thank You

Hi, I saw this solid Acacia plank today at a local flooring store but no one knew the manufacturer because a customer brought it in to find a match and even he doesn’t know where it came from! It’s a light color of what looks like natural and light gray tones with a matte or satin finish. Please help!

Excellent Article, that has proved useful, to me already. However I am unsure on this particular wood. I found this in my schools room of donated wood. I am building a table from it but for another aspect of the project It would help to know the type of wood. I measured the density at about 1070 kg/m^3. This puts it around that of a walnut, but the grain structure seems different. Sawn from very old lumber that was used for some sort of large construction. the exterior weathered wood is grey then black and more cracked on the side… Read more »

Looks like mahogany to me.

Looks like to me like chestnut oak(white oak), just sawn closer to quarter, likely grain affected by large knots that were nearby in the log

I have a drawer unit which I made in the 60’s from afromosia which looks very similar in appearance. However I believe it’s denser than walnut. Afromosia has a tight almost brittle structure which can be difficult to work at times but finishes well. Same family as teak?

Having a difficult time determining what type of wood this mould is made of. Any ideas? and any ideas what it could have been used for?

scandinavian cookie/bread mould,traditional design, examples can be found in stavanger museum collection norway, they went out of fashion/use by mid 20th century in large part due to changes in the home and cooking utensil design. dating them depends on a number of things but it looks to be an older one, possibly 19th century.

A fine site, however I need a little more help identifying the wood in this cane. My great -great grandfather brought it with him from Kildare Co. Ireland in 1831. I have asked cane makers in Ireland and they do not think it is a native irish wood, but are not totally sure either.

Have any ideas?

Bamboo

This picture is of the corner of the dresser sanded. Hope this helps

Looks like oak to me, from the end grain and surface grain showing.

Hi,

I uploaded a picture a few minutes ago but, not sure if it .got through ok so, here’s another that I hope helps identify the wood. It is from a bedroom furniture set which includes Cali-King bed frame, dresser / TV hutch, very wide dresser and night stand. Hope this picture helps.

Thank you,

Do you have any idea what type of wood this flooring might be?

oak

Hello Eric: Fantastic site. Could you have a look at identifying this armoire? It says it was made by Beithcraft Furniture in Scotland, and it was certainly an expensive piece.

Your photo didn’t come through. Repost it?

I was given this piece and have turned it into a chopping board. Any ideas what this could be.? Based in UK if useful to know.

Thanks

Tom

It could be Yew, in which case I would stop using it immediately. Yew is known to leach deadly toxins into food and beverages when used as a container.

Beautiful chopping board. The grain is indicative of Elm to me.. great wood with a tendancy to shake (which is shown above) I have a number of Elm wood pieces and love the table topped with it. Elm is not toxic.

Picture 2. Thanks for your help in me identifying this type of wood.

Hello Eric,

Any idea what kind of wood this is? We found this inside the storage room of an apartment we just moved into. We are located in Germany.

Thank you in advance!

Best regards.

Do you know what kind of wood this is?

It looks like a piece of a Cyprus tree cut across the grain in to a 3″ to 4″ slab and then, they have used Cyprus knees turned upside down to construct the legs.

I stripped this table that was my grandmothers probably made in the 50s from Beals furniture. Does anyone know what kind of what this is? I was thinking maple.

Looks like black cherry to me.

The best guess I can make from just a snapshot would be alder. It doesn’t really look like maple to me, at least, not in this photograph.

This is a cane my dad found, any ideas what plant it came from?

This is a desk I got from my grandmother. She’s had it for as long as I remember, trying to identify what type of wood this is.

I can’t tell from the picture, but at the very least, the color is supposed to mimic black walnut. Whether it’s actually made of black walnut, or just another wood stained with a walnut-colored stain, I can’t say.

Probably palisander veneer on spruce base. Very fashionable in 1930s.

You really know your stuff….any idea what this is?

Can someone help me identify this? It is a very heavy wood – I put some oil on the end to see what the grain looked like. Thanks

Can’t tell from the pic, though the wood has what is known as a ribbon stripe figure. This is caused by interlocked grain in the tree that is most prominently displayed on the quartersawn surface. Probably the most likely and most commonly used wood to have ribbon stripe are various types of mahogany, including sapele. This article may shed more light: https://www.wood-database.com/wood-articles/mahogany-mixups-the-lowdown/

sapele

Hey Tony here just wondering what type of wood my floor is

La caoba tiene un grano más fino. Esta madera se parece al cedro, una madera más ordinaria, con granos largos y profundos.

Hello Eric,

I need to get somebody wood to match these beams – any idea what they are made of?

Thanks,

Paul

I would have to bet that they are oak beams it is a very strong wood and is common in beams

I would say Cedar or yellow pine just because of the cracks and I have used cedar on a similar project and it look’s damn close.

They look like spruce because of the knots and splitting, however it could be eastern white pine too, if it is from that general location.