by Eric Meier

Outline

In sharp contrast to the simple anatomy of softwoods, the hardwoods of the world exhibit a dazzling array of endgrain patterns and intricate motifs; and it’s in this complexity that the challenge (and joy) of wood identification really comes alive. An unknown hardwood sample could be just about anything under the sun, yet as each anatomical feature is considered, anything is narrowed down to something.

That is to say, throughout the identification process, the more observations that can be made and classified about a hardwood sample, the more and more the field of possible candidates narrows. Ultimately, the point is reached where no further refinements can be recorded, and either a clear identification emerges, or a handful of possibilities remain.

As discussed on the page The Truth Behind Wood Identification, a positive identification down to the species level isn’t always possible, but generally, anything can be narrowed down to a more descriptive something, and in many cases, the genus or family of the wood can usually be ascertained. To begin this process, the largest and most conspicuous anatomical elements are examined first.

Vessel elements

When viewed from the endgrain, vessels simply appear to be holes in the wood—what are commonly referred to as pores. In a live tree, vessels serve as the pipelines within the trunk, transporting sap within the tree.

(Softwoods completely lack vessels, and instead rely on tracheids for sap conduction.) Vessel elements are the largest type of cells, and unlike the other hardwood cell types, they can be viewed individually—oftentimes even without any sort of magnification.

For simplicity’s sake, vessel elements will simply be referred to as pores throughout this website.

Hardwoods are initially divided into three main categories according to the arrangement of their pores, commonly called its porosity.

Porosity

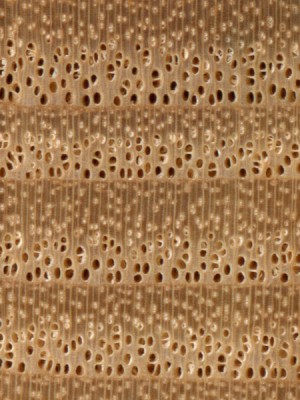

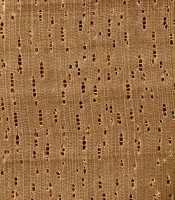

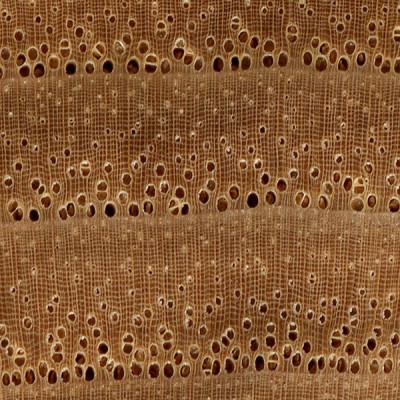

Ring-porous

European Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) is an example of a ring-porous wood, with the earlywood pores clearly forming rings or bands—in this case two to four rows wide.

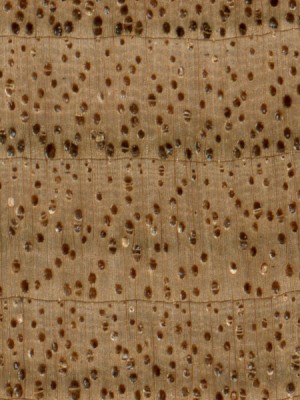

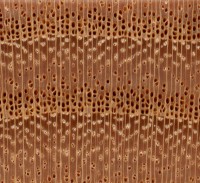

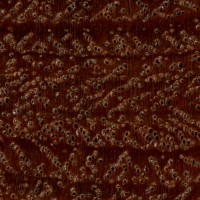

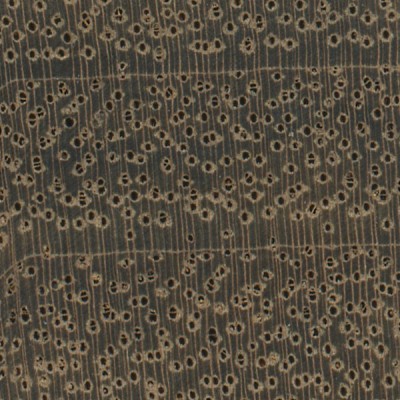

Diffuse-porous

Afzelia (Afzelia spp.) is an example of a diffuse-porous wood, with no clear earlywood-latewood pore arrangement, and no significant difference in pore size.

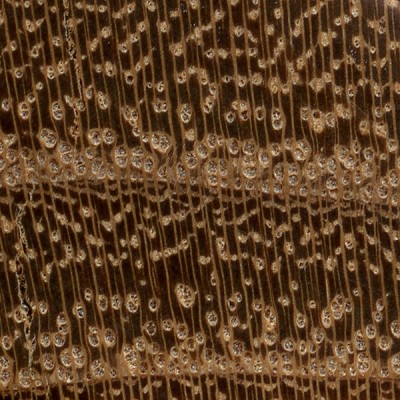

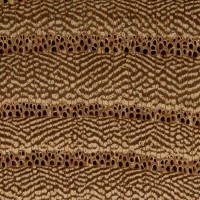

Semi-ring-porous

Butternut (Juglans cinerea) is an example of a semi-ring-porous wood. Although the pores don’t form clear rows, the size gradually decreases from the earlywood to the latewood.

In temperate zones, it’s not unusual for hardwood pores to correspond to the annual growing season, with larger pores forming a band or ring along the earlywood zone. This category of porosity is called ring-porous.

The second category—common in many tropical species—occurs when the pores are distributed evenly throughout the wood. (Growth rings may still be discernible through other cell types, such as parenchyma bands, or a change of color in the wood fibers, but the largest elements—the pores—will be spread out and diffused throughout the wood.) This category of porosity is called diffuse-porous.

Additionally, a third, intermediate arrangement is also seen, which is sometimes difficult to define. It includes wood that has pores that are generally evenly spaced but grade from large to small between growth rings, subtly suggesting growth boundaries. (Wood species with pores of a uniform size that are arranged in weak or broken bands are considered by some sources to be a part of this intermediate category as well.) This intermediate category of porosity is interchangeably called either semi-ring-porous or semi-diffuse-porous; for simplicity’s sake, this group will be referred to as semi-ring-porous throughout this website.

In addition to the foundational three-fold categorization of the pores, there’s also a few other factors pertaining to pores to consider in hardwood identification.

Pores generally occur as single, solitary openings, called solitary pores. When 90% or more of the pores in a wood sample are solitary, it is said to be exclusively solitary, (many species of Eucalyptus are a good example of this). However, despite the commonness of solitary pores, most woods do not have exclusively solitary pores.

Pores also occur in multiples; this appears as two (or more) adjacent pores where the middle wall between them is clearly shared, and is thus considered a pore multiple. When viewed from the endgrain, pore multiples are typically arranged vertically (radially), and are more specifically termed radial multiples. By far the most common pore distribution is a moderate mixture of solitary pores and radial multiples of two to three pores.

Besides the actual pore grouping, pores can also occur in other noteworthy patterns. For instance, Jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) features pores that are exclusively solitary, but they are arranged in diagonal rows forming zigzag patterns. This classification includes pores that are in a more-or-less vertical (radial) orientation.

Another arrangement that is sometimes seen is when the pores occur in straight or wavy tangential bands. This classification includes pores that are in a more-or-less horizontal (tangential) orientation. This pattern is characteristic of all species of Elm (Ulmus spp.), and is sometimes referred to as ulmiform.

It should be noted that with some of these pore arrangements, (particularly tangential bands), they are generally only found in ring-porous woods, and only observed in the latewood portion of the wood. Depending on the growth rate of the tree, the latewood zones can be wider or narrower than usual. This has the effect of either exaggerating or concealing these patterns, so the growth rate of the tree should be taken into consideration as well.

Pore size

Technically, wood pore diameters are measured in micrometers (sometimes called microns), but the scope and scale of such minute scientific measurements can be hard to grasp. Without a means to actually measure the pore diameters (such as with a microscope outfitted with a micrometer eyepiece), knowing the actual measurements isn’t terribly useful.

Instead, it’s more helpful to simply gauge the pore sizes in comparative terms, (i.e., the pores are relatively small, or they are relatively large). This website will simply use the relative terms such as small, medium or large when describing pore sizes.

| Size | Micrometers (µm) |

| Small | < 50 |

| Medium | 50-100 |

| Large | 100-200 |

| Very Large | > 200 |

In ring-porous woods, pore size should indicate both the size of the earlywood pores (usually medium to very large) as well as the size of the latewood pores (usually very small to medium).

Pore frequency

Pore frequency is generally only measured on diffuse-porous woods; if noted, it’s indicated in comparative terms, such as few, or numerous, rather than by precise microscopic terms such as quantity per square millimeter.

| Frequency | Vessels/mm2 |

| Very Few | < 5 |

| Few | 5-20 |

| Moderately Numerous | 20-40 |

| Numerous | 40-100 |

| Very Numerous | > 100 |

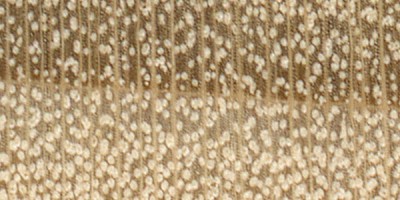

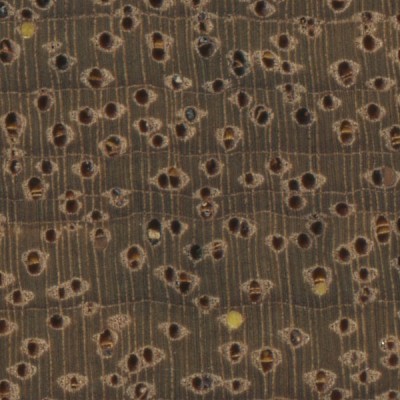

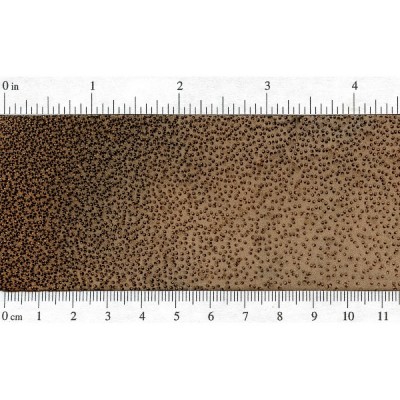

In some instances, considering the pore frequency can prove to be an important distinguishing factor in identification. In the case of distinguishing Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra) from East Indian rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia), one species (D. nigra) has much more infrequent pores, which proves to be a reasonably good discriminator.

The wood sample on the left is Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra), which has very few pores. The sample on the right is East Indian rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia), a close relative which is frequently confused with Brazilian rosewood; its pores are about twice as numerous as the Brazilian sample.

Pore contents

Besides simply considering the size or arrangement of the pores, sometimes it pays to observe what’s actually in them. As sapwood becomes heartwood, certain substances and structures are deposited in the wood cells.

In some cases, pores can become filled with colored gums, resins, or other deposits that can aid in identification. In most species, heartwood deposits tend to be somewhat sporadic, so it shouldn’t be relied upon as a primary identifying feature. The frequency of pore contents, if present, are described using the relative terms, sparse, common, and abundant.

Another common by-product of the conversion of sapwood to heartwood is the appearance of tyloses. Tyloses (singular, tylosis) appear as bubble-like structures that grow into open pores, and in some cases, completely stop-up the pores of the heartwood.

The sample of Panga Panga (Millettia stuhlmannii) has quite a few heartwood deposits; many are a striking yellow, while some are a dark brown.

Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) is a superb example of a wood with pores that are abundantly packed with tyloses.

Some species lack tyloses altogether, while many others have an intermediate distribution ranging from sparse to common, while some species have tyloses in abundance, to the point that nearly every heartwood pore is filled with tyloses. This blockage has the beneficial effect of rendering the pores essentially watertight: a well known example of this is found in White oak (Quercus alba), whose packed pores are commonly used for barrel-making (also known as cooperage).

Parenchyma

In a living tree, the parenchyma contained in the sapwood consists of living tissue that serves as storage cells. Technically, there are a few different types of parenchyma cells seen in wood, (such as those occurring radially in the rays), but far and away the most common type of cells that are designated specifically as parenchyma refer to longitudinal or axial parenchyma, which are oriented along the length of the tree-trunk. All references to parenchyma in this website will be describing axial parenchyma.

Single parenchyma cells are typically too small to be seen individually, but when viewed as a whole, patterns and shapes emerge. Very infrequently, parenchyma is absent or hardly observable, but in most hardwood species, parenchyma forms unique and telling patterns that greatly aid in the identification process. In describing parenchyma, there are two main classifications.

Apotracheal parenchyma

In order to understand this somewhat intimidating scientific term, it may help to consider the English word “trachea,” which refers to a tube or pipe (in this case, a wood pore). Combine this with the Greek prefix “apo,” which means away from or separate, and the meaning becomes clearer.

Apotracheal refers to parenchyma cells that occur separate from the pores. Apotracheal parenchyma can occur as single scattered cells, classified as diffuse parenchyma. These cells are too small to be seen without a microscope. However, in some wood species, several apotracheal parenchyma cells are joined or aggregated together, forming thin but visible tangential lines. This formation is known as diffuse-in-aggregates parenchyma.

Honduran rosewood (Dalbergia stevensonii) displays a multitude of diffuse-in-aggregates parenchyma, typical of many Dalbergia-genus rosewoods. Any apotracheal parenchyma in contact with neighboring pores is incidental.

Paratracheal parenchyma

The counterpart to apotracheal parenchyma is paratracheal parenchyma. The Greek prefix “para” means beside or near, and the classification of paratracheal describes parenchyma that occurs in association with the wood’s pores. Of the two classifications, paratracheal parenchyma exhibits a much wider range of patterns and variations.

Paratracheal parenchyma can occur as single cells bordering a pore, called scanty parenchyma. These cells are too small to be seen individually without a microscope, and along with diffuse parenchyma, will not be given further consideration in this website.

The most basic paratracheal parenchyma formation is a ring or circle of cells surrounding the pore, which is termed vasicentric parenchyma. The term vasicentric is simply a combination of the words vase (suggesting a vessel or pore), and centric, which simply indicates that the parenchyma is centered around the pore. It should be noted that vasicentric parenchyma isn’t always visible with a hand lens. If the pores of a wood species are especially small, (with the parenchyma being even smaller), or if the parenchyma ring is only one cell thick, it may not be clearly visible with a hand lens.

Another form of parenchyma that is closely related to vasicentric is aliform parenchyma. This term literally means “wing-shaped.” Despite the suggestive name, there are actually two primary variants of aliform parenchyma: the first is winged, where short appendages or wings of parenchyma extend from one or both sides of the pore.

One last, somewhat uncommon form of paratracheal parenchyma is sometimes seen in a handful of wood species. Whether the parenchyma occurs in a vasicentric, aliform, or a confluent pattern, when the parenchyma covers only one side of the pore in a semicircular fashion, it is said to be unilateral parenchyma.

When horizontal (tangential) bands of parenchyma occur either as (apotracheal) diffuse-in-aggregates, and/or as extensions of aliform or confluent (paratracheal) parenchyma, it is known as banded parenchyma. Banded parenchyma can be in continuous bands, or it can occur in interrupted or discontinuous bands. The bands can be very thick—constituting over half of the wood’s overall volume in some species—or they can be very thin and hardly visible with a hand lens. The bands can be very numerous and evenly spaced, or they can be very sparse and sporadic.

Other variations of banded parenchyma involve the relationship between the parenchyma (horizontal bands) and the rays (vertical bands). When both the parenchyma and rays occur in thin, closely spaced bands forming a net or grid-like pattern, this is termed reticulate parenchyma.

When the parenchyma occurs in slightly narrower intervals than the rays, appearing as rungs on a ladder, it is termed scalariform parenchyma—so named for its resemblance of scales on a fish or reptile. Wood samples with scalariform parenchyma typically have very wide rays, and short, arched parenchyma bands between the rays.

Rays

Found on practically every wood species, rays can ofttimes serve to provide valuable clues in the identification process. In a living tree, these cells actually run perpendicular to the rest of the wood fibers, and serve to channel nutrients between the cambium, sapwood, and pith. When viewed from the endgrain, rays appear as more-or-less straight, radial (vertical) lines spaced evenly across the wood sample.

Ray width

When viewed under a microscope, ray width can be measured in perfect precision by the number of cells across the ray. Wood species with the thinnest rays measure only one or two cells wide, (called uniseriate, and biseriate, respectively), while some of the widest rays can measure well over a dozen cells wide.

However, when viewed with a hand lens, individual ray cells cannot be counted, and more generic comparative terms, such as narrow, medium, or wide are used to describe the ray width.

| Width | Number of Cells |

| Narrow | 1-3 seriate |

| Medium | 3-5 seriate |

| Wide | 5-10 seriate |

| Very Wide | > 10 seriate |

However, using these generic terms are an imperfect compromise, as the individual rays cells can vary in width, so a narrow uniseriate ray with large cells may visually appear just as wide as a medium-width ray that’s made up of smaller cells.

In addition to noting the average width of the rays, some species also have two distinct sizes of rays present. In the case of hard maple (Acer saccharum), its combination of wide and narrow ray widths can help distinguish it from other soft maples.

The sample of hard maple (Acer saccharum) has two distinct ray widths—some are relatively narrow, while others are wider. The sample silver maple (Acer saccharinum) shows only slight variations in ray width.

Ray spacing

In addition to their width, rays are also measured by their spacing, usually expressed as a quantity per millimeter. However, because of the impracticality of obtaining precise counts per millimeter using only a hand lens, comparative terms will be used.| Spacing | Rays/mm |

| Wide | < 4 |

| Normal | 4-12 |

| Close | > 12 |

The sample of hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) shows a wide ray spacing, while the katalox (Swartzia spp.) has rays that are spaced close together (it may be necessary to view enlargements to see them).

Aggregate rays

Occasionally, some species will have intermittent rays that are many times wider than the rest. These mega-rays are essentially a collection of a number of normal-sized rays grouped together and appearing as one large ray. They are known as aggregate rays.

Perhaps the most well-known commercial lumber in the United States that features aggregate rays is red alder (Alnus rubra). In addition to alder, only a handful of other genera and species exhibit these rays: hornbeam (Carpinus spp.), and some species of sheoak (Allocasuarina and Casuarina spp.) and oak (Quercus spp.) also feature aggregate rays.

Occurrence of the large rays is very sporadic—some samples may not contain any aggregate rays at all, while other pieces will have several. The aggregate rays of red alder are so large and conspicuous that they can be observed on flatsawn surfaces as thin dark streaks, and may be mistaken for defects in the wood.

Noded rays

In some species, the rays will slightly flare out and get wider as they cross a growth ring boundary. This subtle characteristic is referred to as noded rays.

While noded rays are fairly uncommon, they can occasionally serve to help in identifying certain woods. Noded rays are present in sycamore (Platanus spp.), beech (Fagus spp.), basswood (Tilia spp.), and yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera).

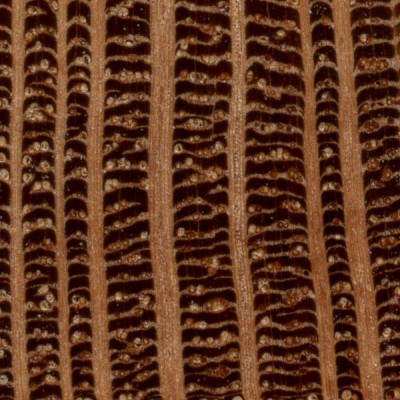

Storied rays

One final characteristic of rays involves examining the flatsawn (tangential) surface of the wood. In some wood species, (particularly those in tropical regions), the rays tend to be aligned in horizontal or diagonal tiers, also referred to as stories. This pattern is called storied rays, and it produces a visual phenomenon known as ripple marks.Even though there’s technically no unevenness in the wood, to the unaided eye, (and at low levels of magnification), storied rays appear as minute stripes of wood alternating between light and dark. In addition to the rays, other anatomical features (such as the parenchyma or the fibers) can also form stories, and therefore produce ripple marks.

In addition to persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)—a temperate species—some notable tropical species with storied structures include: most rosewoods (Dalbergia spp.), Honduran mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), and sapele (Entandrophragma cylindricum).

Wood fibers

In a living tree, hardwood fibers have strong, thick cell walls that mainly serve to support and strengthen the trunk. When viewed from the endgrain, fibers are very small and can’t be seen individually. Instead, fibers can only be distinguished in a broader sense as colored areas which form the backdrop of the wood’s endgrain.

Occasionally, the wood fibers will change in color in correlation with the growing season, providing a means to distinguish the growth ring boundaries in instances where it may not be apparent in the arrangement of pores or marginal parenchyma.

Monocots: a special case

Hardwoods are classified as dicotyledons, (or “dicots” for short) because they have two cotyledons (embryonic leaves). That is to say, when a dicot first emerges from its seed, the seedling will have two leaves. Most of the world’s fruits, vegetables, and fibers are dicots.

However, within the division of Angiosperms (flowering plants) there are also plants that only have one embryonic leaf, called monocotyledons, or “monocots” for short. This important group contains corn, wheat, rice, and all true grasses. In the woodworking world, the most notable monocots are palm and bamboo.

Anatomically, the “wood” of monocots is diverse from both hardwoods and softwoods, and can usually be spotted easily, even without magnification. Viewing the endgrain reveals a fairly simple structure of darker-colored fibrovascular bundles embedded throughout a mass of lighter-colored parenchyma cells. Growth rings, sapwood/heartwood, and rays are all completely absent.

Narrowing most monocots down to even the genus level (let alone to a precise species) is essentially impossible—at least when limited to the anatomical features of the wood itself. There just aren’t enough distinguishing features present to discern between different species. Fortunately, in woodworking and lumber applications, there are generally only a few types of monocots encountered.

Palm

These tropical monocots have no growth rings, and when viewed on end, a palm log will appear as a circular gradient between the darker (and stronger) fibrovascular bundles along the outer edge, and the lighter (and softer) parenchyma structure in the center. Toward the outer wall of the trunk, the density of the wood is the greatest, and gradually becomes lighter, softer, and weaker towards the soft core.

Palm lumber is typically divided into two general categories: red, and black. Red palm is commonly harvested from the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera), but other genera and species are also used. As the name implies, the fibrovascular bundles have a reddish hue. Black palm is harvested from at least five different genera, and is identified by its darker, nearly black fibrovascular bundles, which contrast with the pale grayish brown parenchyma.

The color contrast between the darker fibrovascular bundles and the parenchyma creates a streaked look that is unique to palms. In both endgrain samples, the fibrovascular bundles can clearly be seen without any sort of magnification—a hallmark of monocots.

Bamboo

These fast growing members of the grass family (Poaceae) are very diverse, with hundreds of species encompassing dozens of genera. Unlike trees, bamboo initially grows at full width, with no tapering or horizontal growth.

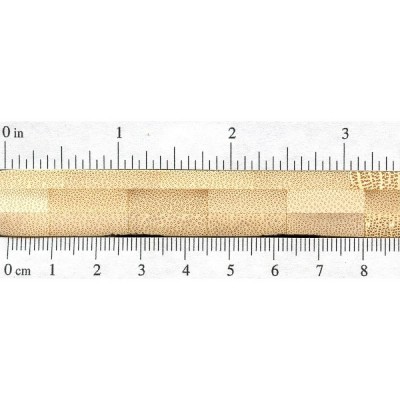

Much like palm, bamboo has fibrovascular bundles that are more concentrated near the edge of the stem—also called the culm—with softer parenchyma grading in toward the inner wall. Bamboo culms are hollow in the center, with closed “nodes” generally occurring every few feet or so.

The sample above is Bamboo (possibly Phyllostachys spp.), which shows subtle interruptions in the grain pattern at the nodes (seen in the right-hand third of the face grain portion). The endgrain also shows smaller strips that have been laminated to form a larger plank.

Note the increasing concentration of fibrovascular bundles near the edge of the endgrain section of Giant Bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper).

Because bamboo has such a small (and hollow) diameter, various techniques are used to manufacture what could be loosely termed as “boards.” Uniformly small strips of bamboo and machined and then glued together to form larger planks, slabs, and plywood for a number of applications, including, flooring, construction, and furniture.

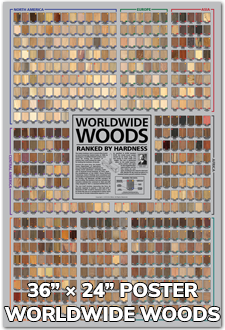

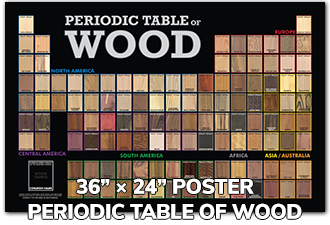

Get the hard copy

Hi Eric,

I came across a 14″ log (crotch piece) in a random pond and couldn’t resist turning it. No smell, generally cut like butter, and is relatively light. Any ideas? Thanks

Pics are: turned bowl, iPhone macro, 10x, 20x.

I’m guessing probably something on this page: https://www.wood-database.com/wood-articles/poplar-cottonwood-and-aspen-whats-what/ Some of these woods can be VERY hard to tell apart though.

Thanks for taking the time to respond, Eric. I appreciate it. Certainly plenty of poplar and cottonwood around here (Williamsburg, VA). Was thinking it might be Black Tupelo, but poplar would make sense too given where I found it.

Hello again!

I am posting another 2 samples of a species and I was wondering if these could be genus Dalbergia (Palissander, Rosewood), Teak or another genus.

Thanks again for any help!

Hello!!

Congratulation for the article and thank you for the informaiton.

If you have any idea of this 2 species?

Could it be genus Dalbergia (Palissander, Rosewood) or Teak?

Thank you in advance.

haloo?? have any idea what their names species

Have a look at this page: https://www.wood-database.com/locust-osage-and-mulberry/

Here is the face grain

Anybody have a clue I was giving this out of a really old barn and I believe it was a post at some point in time It’s very dense and I live in northeast Tennessee

Looks like black locust to me.

Hello and thank you for this good article.

Besides the identification process, does each of these characteristics have an impact on the object we can create with the wood ?

I read your article here which covers a little what I’m asking: https://www.wood-database.com/wood-grain-texture/

If you have any other article which covers more the impact of the wood characteristics on the creation, I would be glad to read it.

Thanks again !

I would say in general, no, the individual anatomy of the wood species don’t seem to have any strong correlation between other characteristics like strength or stability. But I think musical instrument makers have bounced around a lot of theories and ideas of what characteristics go into making a good tonewood, but that is perhaps another discussion.

Yes, anatomical characteristics influence all wood properties, and so do ecological variations within the same species. That is why knowledge about wood anatomy is so important for all activities that use wood as a raw material.

There are numerous articles showing these correlations to different propositus.

Hello Eric,

I’m curious how you get such wonderful photos of the endgrain; obviously need a good scope/camera, but is there any trick to preparing the specimen? I have tried sanding, planing, and sawing but the pores seem to get clogged up or mangled by the tool. Thanks!

There’s two schools of thought on this: the microscope folks and the folks that just sand the wood. I’m in the second camp. It looks like you are cutting the wood from the linear cut lines and rough edges, sort of what a microtome would do to prepare a microscope slide. I just finely sand the endgrain up to about 800 grit, then switch to the foam-backed sanding pads such as Abralon at 1000 grit (I think Festool makes one just like Mirka’s product too). I’ll sometimes go up to 2000 grit for darker woods with the Abralon. The cushioned… Read more »

Surprising to hear from Eric that sanding is actually effective. I did not try sanding while preparing one specimen for identification, assuming that it would not work. What did work, after verifying that my plane irons were sharp and still getting lackluster results, was using a sharp chisel. Bevel-up of course, sometimes having to lift a few degrees to get it to actually bite.

My pics got mixed up, that’s actually the upper-right of the plank, I.e. the 2 boards, etc. on the right. Hopefully, you can still make out the delineation of boards, ring boundaries, and pores. Thanks.

Pulled these 4-board plank off a piano (where it was under a veneer and substrate). I can’t tell whether it’s diffuse pores or semi-diffuse/ring, such that it might indicate the type of wood (e.g. maple/beech/birch or walnut, respectively). It seems clear it’s not ring pores. Any thoughts on the type of wood? Pictured here is a shot of the left 2 boards. One from 1-ft away, showing the 2 boards and plainly showing the ring boundaries; and, the other pic is a closer shot of the distribution of pores on the right board. ‘Love the site. Thanks for all the… Read more »

Can you get a picture of the endgrain? Either sand it or take a thin slice off with a miter saw to clean up the end, then snap a pic.

Thanks, Eric. I had to cut off the end, and sand (applied boiled linseed oil, too). Here’s a couple pics, pre-sand and post-sanding. That raw ‘soft’ wood appearance (and, greener looking) now makes me think poplar – and, it’s not a heavy wood like maple, etc. Thanks for forcing me through a better identification process/assessment. But, please….. let me know if I’m wrong. PS: I’ve deconstructed 5 upright pianos over 100 hrs old each, and poplar was a well-used wood – whether as a substrate to some nice veneers or as a block-laminate wood. So, it wouldn’t surprise me to… Read more »

I agree that the ray fleck seen in the previous photos is also reminiscent of poplar, so it seems a very likely candidate. The last two photos are a ring porous hardwood of some sort, but they don’t appear to be oak. Oak has very wide and conspicuous rays, and I can’t make out any sizeable rays in your photos. Possibly ash or elm?

Thanks Eric. Poplar seems reasonable, i.e. color, weight, “soft” cut, distribution of diffuse pore with rays throughout. The other plank wood definitely appears to be a ring porous wood, but I am easily fooled sometime by the semi-ring porous woods, i.e. ask, to me, seems to have distribution of pores well into the early wood growth; or, true hickory woods, for example, also seem more alike semi-ring porous although defined as ring-porous. Anyway… thanks again. We very much enjoy the site.

I would take a look at what you have compared to Quartersawn Sycamore. Not only it looks very similar and has the same checkerboard pattern and is very common to be mistaken with maple.

Hi eric

its a great website

i wonder if you could help me to identify this wood based on these photos

it really hard, so heavy, kinda mixed redbrown color

maybe it is similar with some kind of Ipe, Massaraduba, Cumaru or else.

Thanks

Those darker black streaks in the second picture remind me more of curupay (aka cebil). Otherwise goncalo alves can also be streaked like that. Getting a clear, finely sanded closeup picture of the endgrain might help.

I am thinking to purchase some french doors, but the seller is not able to identify the type of wood. I am looking for oak. Are you able to confirm if this is oak, or give me clues to what to look for to tell? Thank you,

Hi eric,

I’ve been trying to identify this wood I know it came from a sawmill where they make rocking chairs it is very hard and heavy it has been seasoned but the thing I like about most is the color. Can you please help?

Please clean up the endgrain and expose fresh surface and repost photos. The surface is just too weathered to make out any details.

Thank you for your support but recently I ran into a friend of mine who has a sawmill and he informed me that it was actually poplar wood that I have. He explained to me that some of the wood is only harder and heavier because it has absorbed different minerals from the ground causing the beautiful colors and in turn making the woods so hard to work with.

Do you have any suggestions on working with this type of hardwood?

Poplar is very easy to work, the only problems you might have would be if you wanted to stain it a certain color instead of leaving it natural color. It can absorb stain unevenly and cause blotches, so you’d probably want to look for a gel stain.

Hey Eric!

Your website has become invaluable to me, as I use it all the time when working with different types of woods and just to browse through your articles.

I was wondering if you could help me figure out what this piece of wood is, it has me completely baffled. I received a few planks that are about 3 feet long, 3 inches wide, and half inch height.

Thank you for all the hard work you put into this website and helping others!

Darren

Well, it looks like a diffuse porous tropical hardwood of some sort. Those wide rays look really distinct, and remind me of Cordia species, but that’s just a guess. https://www.wood-database.com/wood-filter/?fwp_genus=cordia

Ipe is my guess

Hi Eric, thanks for your article! I It’s really helpful. Recently, I have been studying on grains as the inspiration for my design, but there is a puzzle I couldn’t solve even after searching for many resources…Do you know how this formed? Why the late wood is elongated with many intervals of early wood? This is a ring-porous wood. Is there something to do with pores? Also, as for the second page, round grains are formed around knots. But why there is a clear boundary between late wood and early wood not early wood to late wood as on the… Read more »

I’m sorry, I don’t understand what you are asking. I can’t see what you are referring to and circled in red. Many ring porous woods form rows that are multiple pores wide, so that may be what you are seeing?

The abruptness of the grain is mostly due to the growth rates of the tree through the seasons. Since it gradually slows down and stops in the fall and into winter, and then abruptly starts back up again in the spring, this is reflected in the wood too.

Hi Eric, This is a great resource. I’m trying to determine what family of wood this sample is from. I’, interested in making a guitar so I’m looking for a stable fairly dense timber similar to Mahogany or Queensland Maple (Australia). I have a few good pieces of this timber I was hoping to use.

What is the weight of the wood? Any noticeable scent when working it? Can you post facegrain pics? Where did it come from?

Great article! Thanks a lot for the documentation.

Does the less pores from Brazillian rosewood has something to do with sound vibration? I guess this is one of the main reason why BR is sought after in musical instruments!

Hi Eric, here is a very clear magnification of a petrified wood specimen, the real piece is only 25 mm by 15 mm. I expect its a piece from Chinchilla, Queensland, Australia. Can you ID the wood? Im not an academic, just an interested person. Its a macro photo with a Samsung A71

I’m afraid I don’t have a chance with fossil wood like this. You might try using NCSU’s Inside Wood system for fossil woods. Maybe you could even contact them and see what they think. https://insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu/search?0

Ok, thanks Eric, appreciated you had a look at it. Ive got no chance at all :-))

Do you have your book for sale I could buy? Amazon currently do not post to Australia, and the bookshops here in Canberra do not have it, and say they cannot get it.

I don’t think it’s available directly to Australia at the moment without using some sort of package forwarding service. Sorry!

Would these pores be solitary, and winged, narrow rays?

Yes, the pores are exclusively solitary, with winged parenchyma. Rays may be closer to medium width, hard to say. At the moment, there’s no matches for those characteristics on the Wood Database. The most common genus with solitary pores is Eucalyptus, but winged parenchyma throws a wrench into the gears.

any idea what wood this may be? this sample is fossil wood, no idea from where, expect its Australia

A fossilized Australian wood. I have about a 0% chance of getting this one! Sorry!

ok, thank you!

I am trying to identify the wood on my table and chairs. It is very hard and looks like it has eyes in several places.

Do you know where I can access to a database of end-grain photos for each type of wood (20-50 samples)?

You can try here: https://insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu/ Definitely not going to get 20-50 though, maybe 5-10 is more reasonable. And they are microscope images, not photos per se.

Can someone tell me what this wood is from the end-grain photos?

Sweetgum or maple or hackberry?

3rd pic

Second pic.

I live in Los Angeles and my neighbors were cutting down a tree so I saved a few horizontal slices (like tree cookies) but I’m not well versed enough in the myriad of wood species to identify it. I have pictures of the unfinished wood with some bark on it still and some of it sanded but un-treated still. I can’t find photos of the tree or its leaves though…. If you recognize it and can let me know what it is, I would greatly appreciate it!!

I have a piece of wood that looks just like this – it is from an Allspice tree – I bought it in Hawaii. Mine does not have the bark, so I can’t compare that.

At first glance I thought this was mahogany, but after looking further, I am thinking walnut. What do you think? I would appreciate your thoughts. Thank you; this is an awesome website.

That definitely shows many of the characteristics of walnut, and not so much mahogany. Since walnut goes blonde as it ages it would make sense that the color of an old chair that was originally either stained reddish-brown or finished with ruby or garnet shellac would exhibit more of the red and less of the brown as it ages.

It is hard to tell conclusively, but I would argue that it has more characteristics of mahogany than walnut. The back rest piece has very tall/long pores that are evenly spaced. Black walnut tends to have much shorter pore lines (perhaps 1/4″?) when viewed on the face grain, while mahogany can have longer pore openings of around 1″.

Found a Henrendon tabletop part piece in trash. Wondering what this wood is. Pretty hard. Had veneer on it.

Hello!! This was found in an old house in Missouri. For the life of me I can’t identify it. It looks like it may have been a flooring piece.

Is it fairly heavy and hard? If so, it’s probably leopardwood.

Hi Eric,

I love your site and use it all the time. What do you use to get the 10x magnification on end-grain? is there a reasonably priced device/microscope you could recommend. I dont seem to be having success with a phone or cheap microscope.

Regards

Brendan

Yes, you can do a search for a jeweler’s loupe. There’s a picture/link to one towards the end of my article on wood identification: https://www.wood-database.com/wood-articles/wood-identification-guide/

Does anyone know what wood this is it is very hard

Sapele?????

The color looks pretty light for sapele. Can you try another pic, this one doesn’t seem to be in focus.

Endgrain pic. Pardon the sanding scratches.

To me, the endgrain is a dead ringer for maple. The bark is somewhat confounding, but there’s a lot of variation across maple trees in terms of bark. Does the wood have much of a scent when being worked? If you’ve worked with cherry before, the faint odor should be recognizable.

Thanks Eric, I couldnt find my post! Thanks for the reply. No I havent worked this wood yet. i have worked with cherry but as you say the endgrain is different. Thanks.

Found this petrified wood in oregon at work. It has tight zigzag growth rings, any idea what type of tree it came from?

Great resources! Ive been studying all available to ID a couple boards I have and what I came up with is maybe wild cherry. The bark says cherry but the endgrain could be cherry or maple. Ive included a couple pics. Am I close?

What kind d of wood is this ?? It is very dense and heavy. Feels waxy after cutting and tried sanding and it barely made a difference. I hit it with a hammer it it made just a small divot..

Can’t tell from the pic, sorry. It appears to be spalted sapwood of some sort. That little bit of dark heartwood in the lower right looks interesting. Doesn’t seem to be your run of the mill stuff.

and here’s a front piece

Here is the end grain

Anyone have any idea what this wood is? It is a vanity that came from an old lodge about 40 years ago. It is heavily stained, can see a nice grain and knots. Will add pics of the end grain and a stripped part.

dear sir,

iam also the wood anatomy experience holder person, trained from FRI,

Dehradun. Iam highly impressed by the deep clearity of the wooden structures. This can be great understanding of wooden species in general.

thanks

rajesh

This is beautiful. I’m guessing Spanish Cedar or Honduran Mahogany. From a garage in Oklahoma. Very lightweight. I can’t pick out a smell. What do you think or know?

Philip,

You can try NCSU’s service:

https://insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu/menu/type/modern/.1

I have a sample of wood from the Blue Mtns near Springwood NSW from a fallen tree. I would like to identify the species. It is red i colour and has small pores without rings and thin <5mm sap. How can I go about this? I have a 10x loop. can i key this out using a series of micro-graphs and working backwards from a list of tree species in the area? Can you advise links? Many thanks Phillip

Hello, I make outdoor hammocks made from wooden dowels. Originally I was using asian birch and treated them with 3 coats of Sikkens HLS (Cetol 1 in North America). This seems to have worked well if there is a re-coat every 2 or 3 years. I am now living in Indonesia, and I want to use teak dowels. Im trying to use scrap pieces from other manufacturers to make the dowel, so they cannot guarantee me premium grade teak. As long as it’s dried 8% – 12% do you think I would have a problem with splitting or cracking with… Read more »