by Eric Meier

The most basic division of elm species is between hard and soft elm. The wood of the hard elms (sometimes referred to as rock elm) generally range from 41 to 47 lbs/ft3, while soft elms typically have a density from 35 to 38 lbs/ft3.

Hard Elms: |

Soft Elms: |

Anatomical Identification

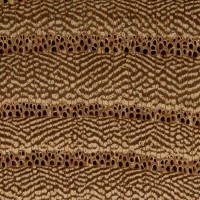

The primary element for distinguishing elm types is found in the earlywood pores. For elms in North America, hard elms are characterized by smaller earlywood pores that are closer in size to the latewood pores. The earlywood is generally in a single, broken row.

|

|

By contrast, soft elms tend to have larger earlywood pores. The earlywood may be one or two rows wide, as in American Elm (Ulmus americana), or two to four pores wide, as in Red Elm (U. rubra).

However, elm species from Europe and Asia do not always follow the same earlywood patterns as the North American species. Most notably, English Elm (U. procera) and Wych Elm (U. glabra) both have single, intermittent rows of smaller earlywood pores, but are considered soft elms.

With the exception of the multiple earlywood rows found in Red Elm, individual species of both hard and soft elms cannot be further separated down to a species level.

Dutch Elm Disease

This fungal disease is spread by elm bark beetles, and has been responsible for the demise of tens of millions of elm trees in North America and Europe. As a result, disease-resistant cultivars and hybrids have been sought out. Hybrid elm trees may have characteristics from either of the parent trees, confounding identification.

Lookalikes

Elm is sometimes confused with ash (Fraxinus spp.), though the two can be separated based on elm’s wavy latewood bands.

This zig-zag pattern, also called ulmiform, is even visible on flatsawn surfaces as minute jagged lines.

Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) is anatomically very similar to elm, though its wide sapwood and grey or yellowish color usually serve to differentiate it from elm.

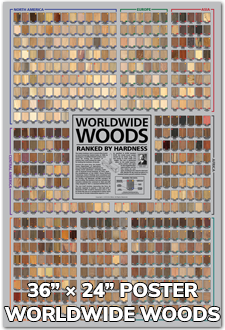

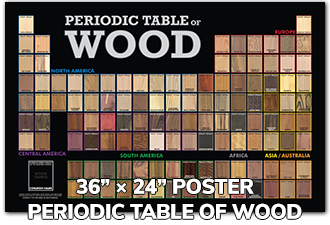

Get the hard copy

Hi I have wood from a tree that was felled 2 yrs after it was pollarded, and then died. I’m pretty sure it’s elm but not sure if it is English or Red Elm. It was felled in the north of England. Any help in identifying would be gratefully received. I’m hoping to use this for turning bowls. ps LOVING your website. Nerd heaven!!!!

Were these all taken from the same tree? The first picture shows earlywood pores in 1 – 1.5 rows deep, while the other pics show multiple rows of pores, so a bit confounding. Also, I’m not sure what the status is with elms in Europe with Dutch elm disease, but in the US we tend to have a lot of newer non-native disease resistant species now, and/or hybrids, making ID a lot more difficult.

Hi. I have a large elm kitchen table from wood felled a few years before Dutch Elm in Oxfordshire. It is wonderful inasmuch as it has survived years of family life during suppers and childrens painting sessions.

The stretchers across the end are going soft in places and as it has become a latter day heirloom we are very keen to stop the rot. It doesn’t appear to be woodworm. It’s more like balsa wood.

Any suggestions gratefully received. Thank you.

Hi Eric, I’m making a bowl of Siberian Elm. I would be happy to send you some samples if you like.

Thanks, I have a sample of Siberian elm, but have not added the info/pics to the site just yet. These are good pictures for the interim.

Any articles that I’ve read about elm state that the wood is easily subject to rapid decay, if left exposed. Nevertheless, elm was the wood of preference for structural components of 17th and early 18th century ships made in Britain. Of particular note was the choice of elm for ships’ keels. Can someone please clarify this for me?

I have worked with both Red Elm and American Elm. American Elm decays quickly and is challenging to split. Red Elm on the other hand decays much slower and splits easily. The two versions of Elm have extremely different characteristics in decay and interlocking grain.

Thanks for the input, Ron. I imagine then that the English Elm is more likely of a “RED” variety. Further research has also indicated that large Elm posts were often the choice for bridge piles ( in England), apparently for the same reason.

im in western Illinois for firewood i like what we call red elm dead its redish in color inside these trees grow to about 60 ft die and all limbs fall off the elm will stand for about 5 yrs. then the roots rot and tree falls over . base trunk about 16″ . tree is sraight dead tree on ground is barkless and wood is very hard reddish inside best firewood we only cut dead fall downs what name is it?

Does it split easily? The 8 month dead 80+ foot elm i have down here in s/e texas WONT split

I asked my partner not to cut it up, as there was approx.40′ of straight knot free 16″ + “SAW LOG”

but, nobody listens anymore?

One thing I’ve noticed about this wood is , it is extremely strong and very flexible, i can push over a 4″ sapling with the tractor bucket and try to chop it off with the cutting edge to no avail, and after i continue it springs right back up like its giving me the finger!!pluckyew!!

I am a woodworker from the UK who has worked with English Elm, I discovered some boards that had been in plastic amongst other timbers that had rotted from 20 years of rain. The elm sapwood was rotted but the rest was fine albeit with a little woodworm on the outer weathered surfaces. The one reason it is no longer used is Dutch elm disease which sadly wiped out most of the magnificent trees within a few decades. If you want a comparison I would say it is as durable as untreated iroko in real terms and among the most… Read more »

Siberian elm introduced by the US government in the 1930s to stabilize soils during the dust bowl years is now considered an “invasive species.” Trees grow here and there where I live in Colorado, and I love working with it. In spite of an interlocked grain, it seems to work well and has beautiful appearance in a variety of smaller items. It seems to be very hard and has a smooth sanded feel like hard maple. A spalted log sitting in a gully for a couple of decades suggests that it is fairly rot resistant, and a large serving spoon… Read more »

I realize this is an old post but I stumbled upon a Siberian Elm that we took down to make way for a neighbor’s fence. I cut it up and used it for amazing blocks for my little kids! Its so dense and smooth! What else would give this same texture?

Where I live in southeast Idaho, most of the elm is Siberian Elm (Ulmus pulmila). Echoing Anthony a few comments above, I would love to have some info on this species of Elm.

Ulmus pumila – Siberian Elm should be added to the database since it is rather common here in the States. Siberian Elm is often mistaken with Ulmus parvifolia – Chinese Elm even though they look completely different.

I would like to know how to tell the difference in trees by grain bark and leaves

Just to add to bunch of anecdotes here. Last year I purchased blindly n-th-hand (I suspect ‘n’ is more than 2) pieces of veneer. It claimed to be oak, but after I received my parcel, it turns definitely not. First I thought it was ash, often mistaken with oak, but after having read here Eric’s article about elms mentioning ulmiform, it appeared that pieces were elm – I used exact those portions of veneer with many of that spectacular ziggzagged patterns! Of course, I almost suspected it earlier, given its colour (astonishingly alike my local elm wood samples), but thought… Read more »